Price of Independence: December 1986 Uprising in Almaty

VoxPopuli and Карлыгаш Нуржан

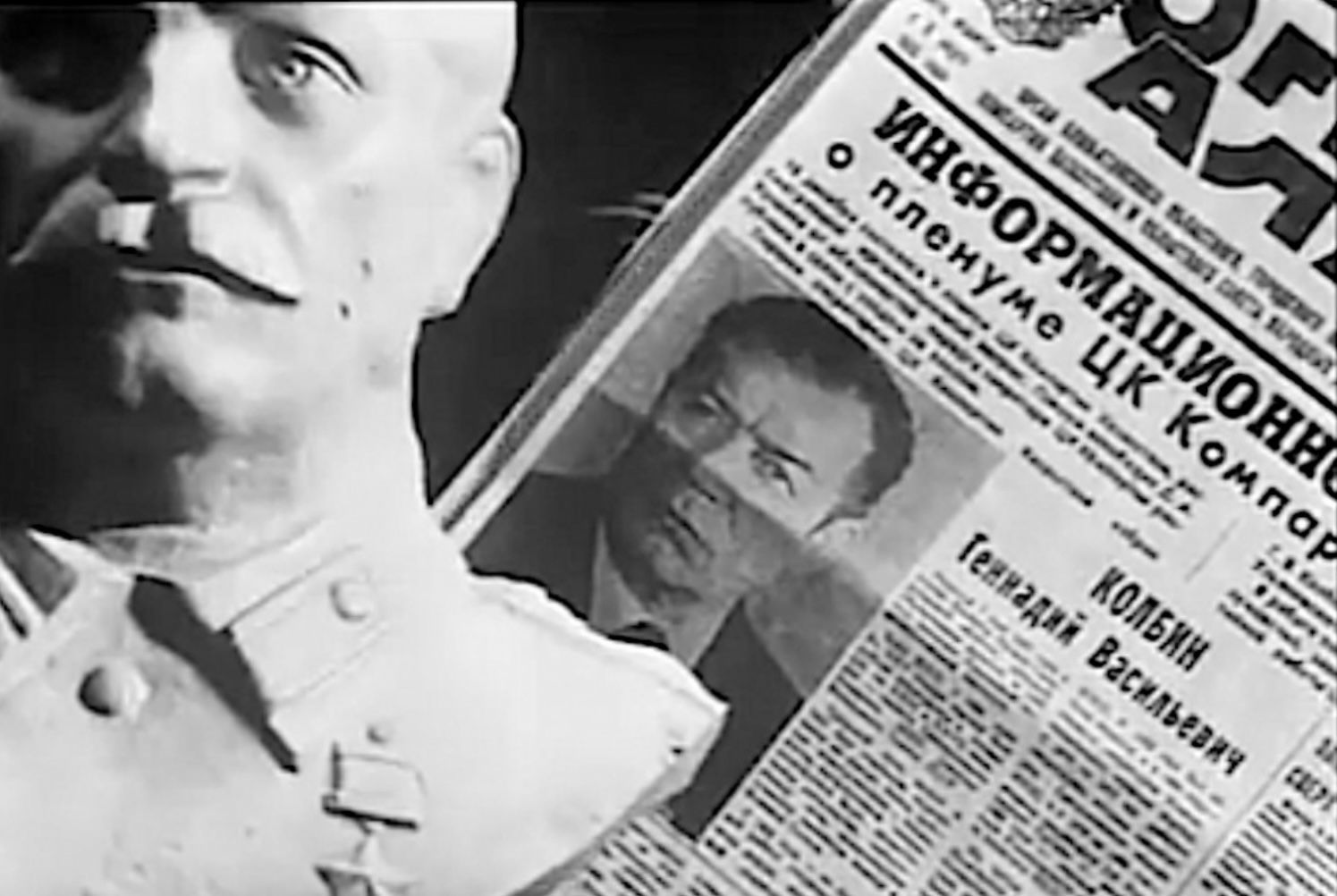

This year marks 39 years since the notorious “December events”. On 16 December 1986, immediately after the decision of the Plenum of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Kazakhstan, an unknown figure recommended by Moscow, Gennady Kolbin, was appointed First Secretary of the Republic. That same day, several hundred students and young workers took to Brezhnev Square (now Independence Square) with the slogan “Every people must have its own leader!”, demanding that the Plenum’s decision be revoked. What started as a peaceful march turned into a brutal clash between police and students and lasted three days. Demonstrations also broke out in other cities of Kazakhstan. The December 1986 events entered the country’s history as a harbinger of the independence of the Republic of Kazakhstan (the photos show still frames taken from newsreels of the 1986 December uprising).

A few days after the unrest, the local press wrote: “... incited by nationalist-minded elements, groups of students grossly violated public order, started fires and riots, and beat innocent citizens. All this was accompanied by demagogic slogans about allegedly offended national dignity of the Kazakhs...” (“Nam gorko” – ‘We are bitter’, Vechernyaya Alma-Ata newspaper, 27.12.1986)

“...What right did these hooligans, most of whom were under the influence of alcohol and drugs, have...?” (“Nam gorko”, Vechernyaya Alma-Ata, 27.12.1986)

“Competent authorities are conducting an investigation against the instigators of disorder, hooligan and parasitic elements...” (“Politburo of the CPSU” section, Kazakhstanskaya Pravda newspaper, 27.12.1986)

“The actions of nationalist-minded elements who are trying to intoxicate the student youth with nationalist frenzy are causing righteous indignation among the working people of Alma-Ata. City and district party and Komsomol activists, labour collectives, and the broader public have decisively condemned the groundless actions of this group of students and actively participated in the measures carried out by Soviet and party bodies.” (“Chuzhie na ploshchadi” – “Strangers on the square”, Ogni Alatau newspaper, 26.12.1986)

“All that was written in the newspapers at the time was slander,” recalls Kurmangazy Rakhmetov. “Among us there were no alcoholics, no drug addicts, no people driven by nationalist hatred. At the rally we only wanted an explanation from our leaders: why had they appointed as First Secretary a man from outside, who did not know our country or its problems? Instead of listening to us, they punished us harshly.”

“At 16 I graduated from an experimental boarding school in Almaty with a gold medal. Russian was difficult for me, and without it I could only hope for a technical major. So I joined the army, hoping to learn the language there. Returning in 1986, I passed one exam and was automatically enrolled in a special physics programme at KazGU. Instruction was in English, so I had to take extra lessons. Because of my excellent grades I was soon appointed Komsomol organiser for the first-year students.”

“The first time I went to the square was on 17 December, simply out of curiosity. Students were demanding that Kunaev come out to the tribune and explain everything. Perhaps if he had appeared, things would have turned out differently. A delegation was sent into the Central Committee building, but the guys never returned. Among them was a woman with a child, what happened to them no one knows to this day. This unnerved the crowd; a conflict began between soldiers and students. After all the injustice I witnessed in the square and in the city streets, I began to ask myself: ‘Why, living in my own country, am I being humiliated? Why has my native language become an outcast among my own people?’ A day later, on 19 December, we left the institute with slogans in Kazakh: ‘Long live Lenin’s national policy!’”

“But we never made it to the square: police caught up with us on the way. Everyone was forced onto buses; I was lucky enough to escape. A few days later they came for me, and I had no idea what lay ahead. For taking part in the protest I was automatically expelled from the Komsomol and sentenced to seven years. The eighteen minutes spent on the Plenum decision to replace Kunaev with Kolbin predetermined our future and completely changed our outlook. We never imagined such a thing was possible here; we blindly believed in perestroika. Remembering those days is painful; you relive everything. I saw it all. And there was a lot...”

На снимке один из участников декабрьских событий Ермухан Жунисхан. На тот момент ему было 20 лет

Today, Yermukhan Zhuniskhan is an academician of the Academy of Arts and a member of the Union of Artists of Kazakhstan. He remembers everything as if it happened yesterday.

“In 1986 I had just entered the art and graphics faculty of Abai State Pedagogical Institute, but only a few months later I was expelled for taking part in the December uprising. On the eve of 16 December there were already rumours about Kolbin’s appointment; we discussed the injustice of this decision in our classroom. I should note we were not against a Russian leader; we were against a person who did not come from Kazakhstan. That day all our discontent remained just talk.”

“The next day, 16 December, while we were in a painting class, we heard voices and noise in the street. When we came down to the entrance, we saw young people gathered there. From them we learned that Kunaev had been dismissed and Kolbin appointed. The youth called on us to join the rally on the square. I remember my classmates and I went just as we were – without coats or hats. Together with the demonstrators we walked down to Gogol Street and headed to the Women’s Pedagogical Institute. Then we moved up along Baytursynov Street (then Kosmonavtov). Before reaching Abay Street, a police car began to follow us. For us this was a peaceful march: there were no anti-Russian or anti-Soviet slogans. When I looked back, I saw no end to our column.”

“On the square there were already many people with banners: ‘Every people must have its own leader!’, ‘Lenin is alive!’. At about three o’clock, leaders of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Kazakhstan came out and rudely ordered everyone to go back to where they came from. But demonstrators ignored them. It was cold. My classmates and I decided to go back to the dorm, warm up and grab a bite. When we returned around seven, the square had turned into a battlefield: several fire engines were burning, students and soldiers were fighting, someone had brought a flare gun and fired it at the Central Committee building. It all looked like a war. Police cordoned off the building, and we started throwing stones at it. Soldiers began to disperse the demonstrators, and then the real massacre began – they didn’t spare even the girls. Soldiers had batons and shields; we had nothing and were forced to retreat. Later I was told that before we returned they had started spraying demonstrators with ice-cold water, which only further inflamed the crowd’s anger.”

“On 17 December we gathered on the square again,” Zhuniskhan continues. “The university administration had locked the doors, but we climbed out through the windows. The square was packed. Young men took turns speaking, openly saying that appointing a person from outside was wrong; we needed our own leader, regardless of nationality, as long as he was from Kazakhstan. They cited Lenin’s ideology of equality. Around us stood ‘druzhinniki’ – volunteer patrols. They were recruited from ordinary citizens, wore red armbands, and carried pieces of metal rebar. Newspapers later wrote that the demonstrators themselves brought the rebar to the square – that was a lie. Around eleven in the morning several armoured personnel carriers drove onto the square. Ten or so men sat on each, all in helmets and carrying sapper shovels. I clearly remember one scene: a girl lying on the ground with blood trickling from her throat. White snow all around and such bright red blood...”

“People started to scatter. Some ran into the Okean grocery store, a few jumped behind the counters, some went down into the basement, and I ran down the corridor. Behind me a woman shouted: ‘Not that way! There is no exit there!’ At the end of the corridor soldiers caught up with me. Two blows to the head with a baton – and I lost consciousness. I came to when they were dragging me by the legs along the corridor. At the exit a man in uniform punched me in the face; I fell to my haunches and about ten border-guard cadets started beating me – some with rebar, some with batons, some with sticks, some with shovels. Good thing when they hit me on the head with the shovel it was flat side down, not the edge. Another cadet ran up in time, stopped the beating and, in fact, saved my life. They put me and other students on a bus and took us to the district police station. On the way police officers let those with documents go. My student ID had been taken before I boarded the bus, so I rode all the way. When we arrived, a ‘corridor’ of baton-wielding policemen lined the path from the bus to the entrance. About forty of us were crammed into a cell for two. Then came interrogation. I was released only at dawn. I walked back to the dorm on foot and collapsed into bed. Turned out I had a concussion and lay there for three days. On the third day I was summoned to the dean’s office and informed I was expelled for active participation in mass riots and for leaving classes without permission, disrupting lessons.”

“After that they summoned me to the prosecutor’s office, showed me albums with photographs of the demonstrators and hinted that I would be reinstated in the Komsomol and at the institute if I identified my own people,” the artist recalls. “Flipping through the album, I recognised my classmates and even my physical education teacher, but I did not show that I knew them. I was only able to enrol at the same institute again two years later.”

“The December events did not break me as a person,” says Zhuniskhan. “The only reminder of those days were the constant headaches that kept me from working and living normally. After years of treatment they gradually subsided, though I still need to continue. Despite the past I keep moving forward, painting; my works are in private collections around the world. I’m active in the Union of Artists of Kazakhstan and, since 2011, head the public foundation ‘Zhetisulıq zheltoksandytar’ in Taldykorgan. I have a family who understands and supports me.”

Калдыкыз Аттемова, учитель физики и математики, тоже в те дни была на площади.

“On 16 December we had a political economy class. Instead of our usual lecturer, a teacher from KazGU came. He told us about that day’s Plenum, where Kolbin had been unanimously approved as First Secretary, and even wrote his surname on the board. A heated debate broke out in the classroom.”

“All evening we waited for news. Only the next morning, 17 December, they brought us a newspaper with a large photo of Gennady Kolbin and an article on the front page about his election. My girlfriends and I tore the paper up. The entire dorm discussed nothing but this. Instead of going to classes we went to the square. No one forced us – we simply wanted answers from the authorities. There was almost no one on the square, only police. They told us that at 16:00 there would be a demonstration and we could get our answers then. When we returned at the appointed time, the square was already full.”

“At the university they initially tried to keep us from going, warning we would be punished. ‘Why punish us?’ we asked. ‘We just want to know why Kunaev was removed and who this Kolbin is.’ We stood for about two hours, singing songs to pass the time. It grew dark, but we still had no answers. Police began to disperse the crowd. A general stood just a few steps away, asking us to leave. And then, I didn’t even understand what happened: a young man ran up, shouting, ‘Girls, go! They’re beating everyone, they show no mercy, run!’”

“I couldn’t understand what we had done to deserve a beating. Suddenly I saw a line of police in helmets, with shields and batons, moving toward us like a wall. I tried to run but tripped and fell. A mustachioed officer, about 30–35 years old, ran up; he had a baton in each hand. Cursing, he started beating me on the head. I blacked out. When I came to, they were dragging me by the hair along the asphalt, and I felt warmth beneath me – in my unconscious state I had lost control of my bladder.”

“When I opened my eyes, there were only hats on the ground, blood, barking dogs, black smoke and fire. They dragged me to a yellow truck; one of the soldiers kicked me from behind. Inside I saw young guys piled up like logs. They threw me on top. We were taken to a police station, where a fifth-year law student started questioning me. During the interrogation a man came in and ordered him to call an ambulance. They took me to a hospital. The doctors treated my wounds superficially and sent me back to the police. In a tiny cell there were already 54 other girls. All had been beaten. One had holes on her back from hairpins; another had marks from being whipped with chains. I had no strength to talk to anyone...”

“After three days of interrogation and a forensic examination, I was taken back to the dorm. At the institute they told me to stay away from classes; I didn’t yet know I had already been expelled from both the Komsomol and the institute. A few days later, on the 24th, they came for me again and took me to the Kalinin district police station, read the verdict and sentenced me to ten days in jail. Instead they kept me for twenty. I was released only on 13 January. My parents came to pick me up; we were about to leave when I fainted right in the dorm. They called an ambulance, but instead a special team from a psychiatric hospital arrived. I woke up already in a psychiatric clinic at the corner of Abai and Masanchi, where I spent 14 days.”

“I tried to throw away the pills without being noticed, but there was no way to avoid injections. The worst part (Kaldykyz begins to cry) is that I didn’t immediately understand what they were doing when they put me in a gynaecological chair and started using metal instruments until I saw blood. Only later did I learn that they deliberately tore the hymen of all the girls involved in the December events. My parents took me from the hospital. I had a haematoma on my head; I needed surgery, but in Kazakhstan no doctor dared to operate on a December protester, so we had to go to Tashkent. There Moscow surgeons operated on me. They later said I had survived by sheer miracle. A year later I received a letter from the rector’s office. From the very beginning my adviser, Mukashev Kanat, had spoken up for me, and thanks to him I was able to finish the institute. He told me, ‘When the time comes, everything will be different, and your names will be entered into a Red Book of Honour.’ My parents died young. After all I went through, my mother developed seizures.”

“In 2004, while restoring my documents, the newspapers began to write about me. The parents of my students read the articles and complained to the principal of School No. 13: ‘Why does such a teacher work here? She was in a psychiatric hospital – how can you let her teach children?’ I tried to explain that I had been healthy and was forced into that hospital, but a year later I was nevertheless pushed out of the school. Now I teach in a Kazakh school.”

“At the time I was 24 and worked at the Yuri Gagarin garment factory,” says another participant in the December events, Akkumys. “1986 was the hardest year for young people: we were humiliated for not knowing Russian. The December events were the days when we needed to show ourselves and raise our heads. But our protest was not an act of nationalism.”

“In the night between 17 and 18 December, everything happened as in a terrible war movie. Searchlights shone on us, we were doused with freezing water, dogs were set on us, people attacked us with metal bars. After they beat me, I lost consciousness. I later learned what happened next from my friend. We were loaded into a garbage truck and taken to a dump, where they simply threw us out. People who collected glass bottles there helped everyone climb out of the pit. All this time I remained unconscious; my friend didn’t abandon me and dragged me on her back. Later a police officer helped us reach the emergency department of City Hospital No. 12.”

“When I was discharged, I was walking down the stairs when the elderly lift attendant saw me and cried out, ‘Oh, the long-liver! It was I who took you when you were in the morgue...’ She told me that when we arrived at the emergency department, doctors examined me, declared me dead and sent me to the morgue. Three days later she found me there. She herself could not explain how she ended up in the morgue – as if some force had pushed her inside. The light was on, and she saw me sitting on the stretcher. She was the one who took me from the morgue back to the ward.”

“All medical records from 1985 to 1995 had been destroyed. The only proof that I had been in the hospital were entries in the logbook. That allowed me to restore my documents. On 30 November 2006, I received a phone call from the akimat: they happily informed me that, in honour of the 20th anniversary of the December events, the state was allocating an apartment to me and asked me to bring all necessary papers. I ran to the akimat the same day, but I still haven’t received the promised flat. I have appealed everywhere, until one day I got a phone call at home: they told me to keep quiet or I would regret it. But I am not afraid; I have already been to the other side.”

Gulbira Paninova (left) and Gulnara Abylkairova worked as seamstresses at a hat factory that year. Gulbira was a Komsomol organiser, and Gulnara was a team leader.

“I was returning from classes and heard two older women speaking harshly about the students who had gone to the square,” says Gulbira. “I stepped in and scolded them for their remarks. In our dorm all the girls were getting ready to go to the square. Everyone went: Kazakh, Russian, Uighur, Tatar girls alike. The next day, 18 December, we made leaflets reading ‘Every people must have its own leader! Down with Kolbin!’. At first the rally was peaceful, but after they sprayed us with water unrest began among the demonstrators (in the photo: Gulbira with her fellow workers from the workshop, all later convicted for participating in the rally, autumn 1986).”

“For taking part in the protest and distributing leaflets, I was sentenced to two years, and my friend Gulnara to three. In prison we were placed together with thieves and murderers. Even the criminals initially treated us, the December girls, with hostility. We worked eight hours a day at the prison sewing factory and then carried bricks and cement at construction sites. Gulnara’s younger brother was also sentenced to five years – it was a terrible blow for their parents (in the photo: Gulnara Abylkairova at work, autumn 1986).”

A still frame from archival footage. People watching the demonstration on the square.

Many could observe what was happening from balconies overlooking the square.

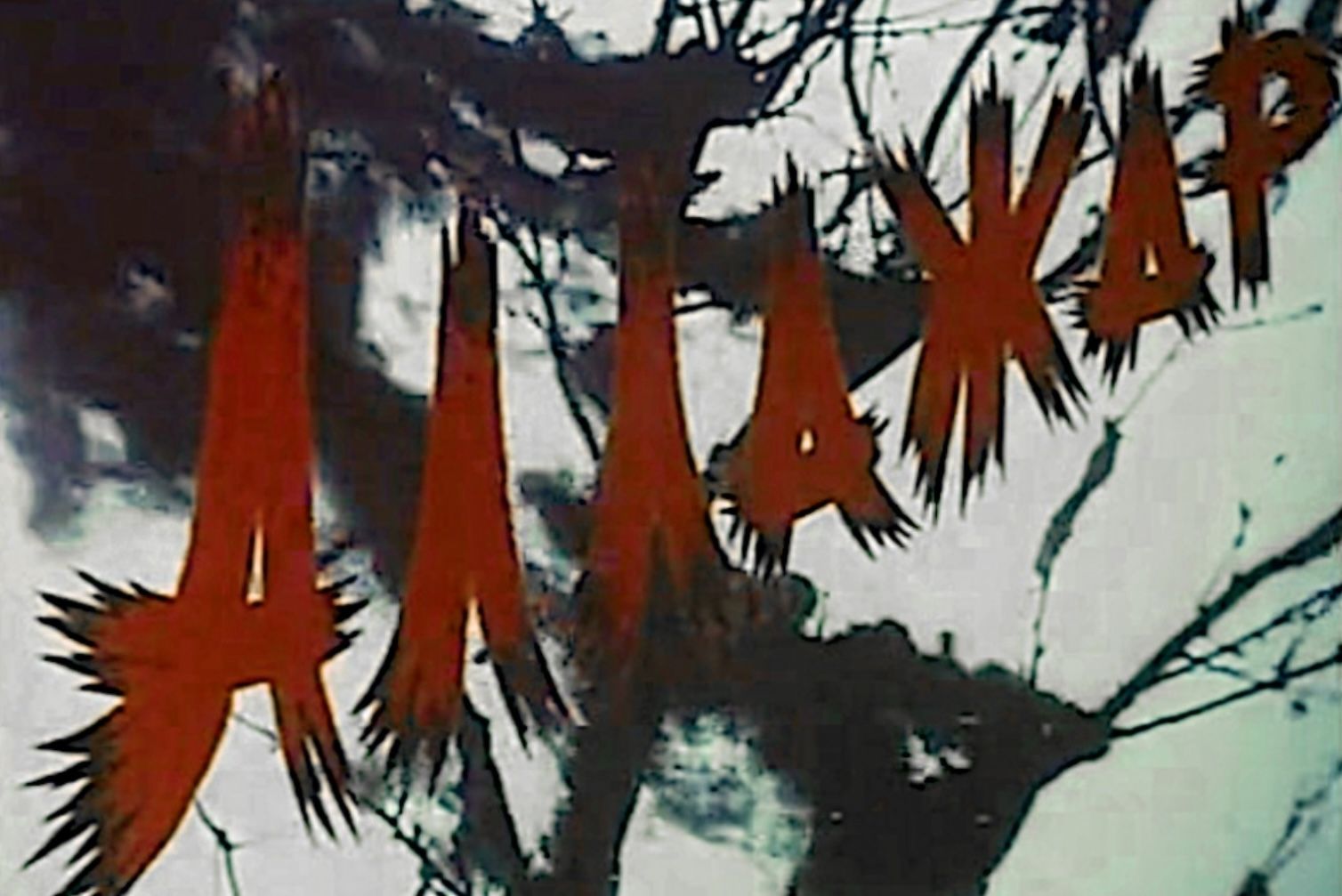

One of the most important links connected to the December events is the film Allazhar. Director Kaldybai Abenov spent almost eight years – from 1988 to 1996 – making it. In the opinion of the December protesters themselves, the film truthfully reflects the events that took place 25 years earlier.

“I, too, was on the square on the 17th,” Abenov recalls. “During the day there was still a peaceful rally, and in the evening I flew to Moscow together with Asanali Ashimov. Tickets had been bought three weeks in advance – precisely for the evening of 17 December. Now I think the Almighty saved me for a reason. Since 1988 I have been living with this film; the burden is heavy, but it is a responsibility.”

“To shoot the film I invited my co-author from Moscow, Alexander Lapshin. Our first task was to find the young people who had been on the square and start shooting from their own stories – what happened to them, what kind of abuse they endured. There had to be no lies. In 1988 repression continued, trials were still underway, and many people were afraid of us, thinking we were from the KGB. By New Year we still hadn’t found anyone, so we continued searching the following year. That was when students who had served their sentences began to be released: Khasen Kozha-Akhmet, Amanzhol Naliyev, Zhansaya Sabitova, Yerlan Dakelbaev. We began filming with them.”

The plot of the film closely echoes the real story of student Kairat Ryskulbekov, who died under unclear circumstances in a transit prison. The main character Azamat is played by a young Akhan Sataev (a scene from Allazhar when the verdict is being read).

A real photograph from the courtroom taken by Yuri Becker on 16 June 1987 for the KazTAG news agency. On the defendants’ bench from left to right: E. Kopesbayev, T. Tashenov, K. Ryskulbekov, K. Kuzembayev. After this “provocative” picture was published – the Central Committee believed it portrayed Kairat as a hero – the leadership of KazTAG, along with the photographer and the editor of the Zhetysu newspaper, were fired and barred from professional work for many years.

“In my film,” the director says, “I used genuine footage from the December uprising. These reels were given to me by Zhanna Munaytbasova, head of the Technical Control Department at Kazakhfilm. What she did was essentially an act of heroism. Risking her job, she smuggled four cans of newsreel film out of the studio under her skirt.”

“On 20 May 1989, at Kazakhfilm, in a circle of December protesters, we first publicly declared that we were the ‘Zheltoksan’ public movement. At the time I had no idea my phone was tapped and I was under surveillance. I was assigned a fake administrator, and as soon as he appeared, my problems began. I was constantly summoned for interrogations; the investigators had a copy of my script and tried to persuade me that there had been no casualties, no beatings, no people taken outside the city.”

“When they realised I would not go along, they started to interfere. They tried to freeze the project by cutting off funding. So I opened my own studio, Bars. Friends lent me money, and with it I bought a whole train car of film stock. It required special storage conditions available only at Kazakhfilm. Studio management found reasons to fine me almost daily. Within three months I was bankrupt. I even had to ‘steal’ my own film stock, loading it onto two KAMAZ trucks and driving it away before they came up with something else.”

“Unfortunately, many unique shots made for the film were stolen, including footage of a western burial site near Boraldai. I went there as a director to see it with my own eyes. It was a trench about 800 by 1.5 metres, with three markers: a five-pointed star at one end, a crescent in the middle, and an Orthodox cross at the other. We questioned the site’s supervisor, an ethnic German who had worked there since 1985; our conversation was filmed. He said the trench appeared in December 1986 but tried to deny that it contained the bodies of December protesters.”

“So I asked him: ‘In December of that year, were there any other mass executions, epidemics, or deaths on such a scale?’ He replied, ‘No.’ I asked everyone to step out, and when we were alone, he said: ‘Comrade director, you made a big mistake. You should have come here not with microphones and cameras, but with a crate of vodka. Then the burial workers would have told you the whole truth about what happened – a truth that would make your hair stand not just on end but catch fire.’ Sadly, a year before the collapse of the USSR, the site was bulldozed flat and the bodies were reburied in an unknown location.”

“After the premiere of Allazhar in Pavlodar, some KGB and Interior Ministry colonels wanted to talk to me: ‘Comrade director, you say you saw a trench with over a thousand people in it. Why, then, do their relatives not search for them?’ I answered, ‘You are right, but there are three reasons for this silence. The first is fear. People were so terrorised that they cannot speak openly. We found a man whose son had died on the square. In private he admitted his son was a victim of those days, but flatly refused to sign any documents or testify in court. The second reason is bribery. One father, having received a high-ranking post, turned a blind eye to his son’s death. The third is destruction of evidence. A second-year KazGU student is killed on the square by a sapper shovel, yet her parents are told she died of a heart attack. When we began to investigate, we found that all her university records had disappeared. Only her student ID remained as proof.’”

“In addition to filming, we engaged in public work as the Zheltoksan movement. In 1989 we wrote to the Central Committee of the CPSU and the city executive committee, informing them that on 17 December we planned to go to the square to lay flowers for the dead and recite a prayer from the Quran. Negotiations lasted several days. Eventually they allowed us to hold a meeting, but not on the square – only in the assembly hall of the medical institute. After the December protesters spoke about what they had endured, the entire hall shouted: ‘Long live Zheltoksan! Down with Kolbin! Down with the CPSU Central Committee!’ As a result, we managed to hold meetings in all universities, and on 17 December we laid flowers on the square and recited a prayer. It was our first victory.”

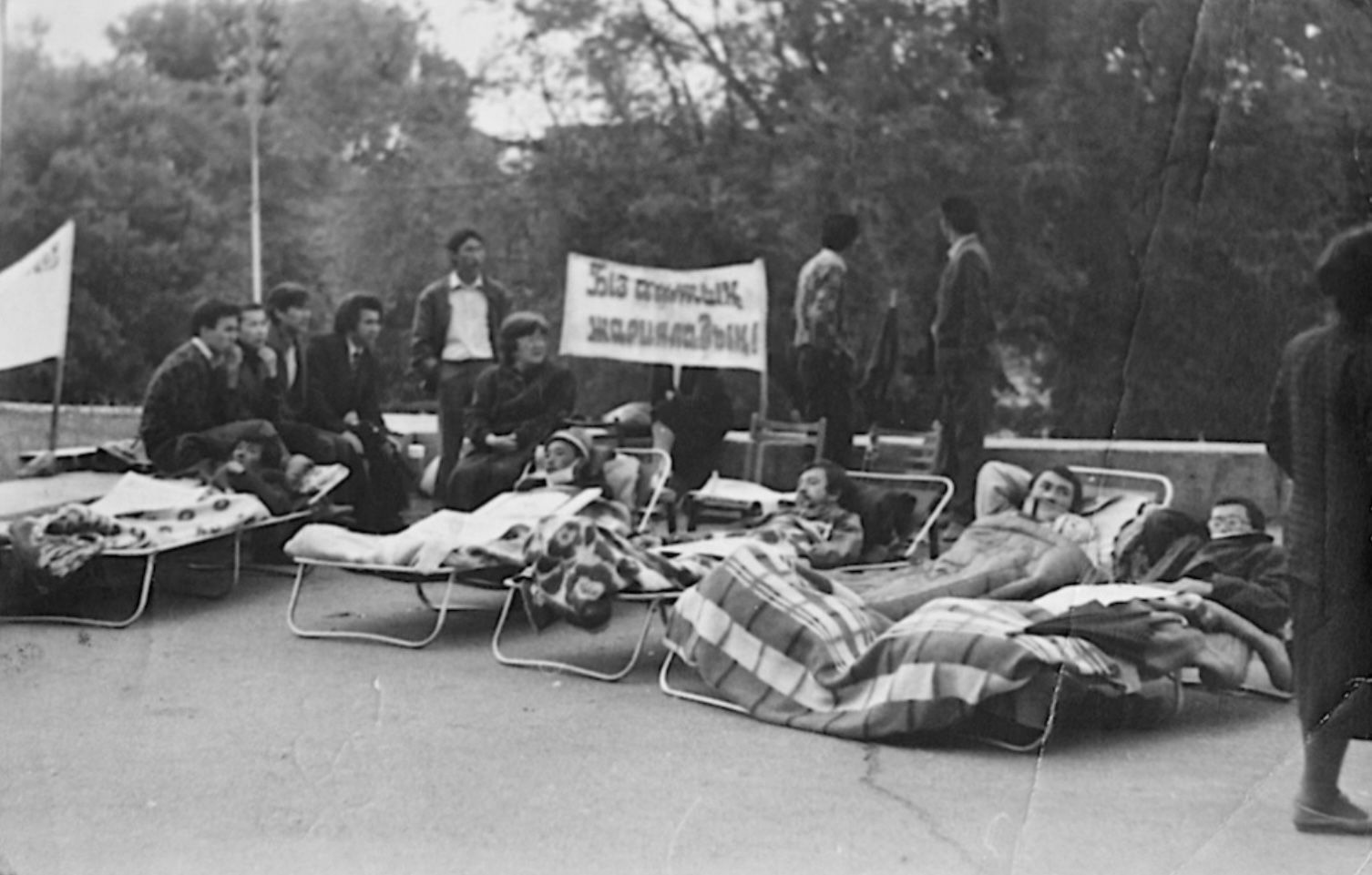

“We didn’t stop there. On 14 May 1990 we launched a hunger strike, and by 18 May we had secured the release of all imprisoned December protesters except Abdykulov Myrzagali, who had been sentenced to death. Two days later, exactly one year after the founding of our movement, we held the first Congress of December protesters at the House of Cinema (photo from Kurmangazy Rakhmetov’s personal archive).”

“On 12 December 1991, the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan issued a decree fully rehabilitating those subjected to criminal, administrative and disciplinary punishment for participating in the events of 17–18 December 1986. But even today these events have still not been granted official status as the December Uprising.”

The report uses still frames from newsreels of the December events.

The original version of this material was published on Voxpopuli.kz before the site closed in 2023. The author restored the text from a personal archive in order to preserve documentary and historical materials.

A detailed account of the 1986 December protest in Almaty and the people whose lives were forever changed. Photo story for Shanger.kz

The revival of the iconic Aqqu Café brings back a cherished cultural memory for Almaty residents and preserves the city’s heritage.

Shangerei Bokey shaped early Kazakh visual culture as the first photographer and educator. Story by Karlygash Nurzhan for Shanger.kz

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!