Era of “Cannibals”: Karlag and the Repression Victims

VoxPopuli and Karla Nur

In 1931, a state farm called “Giant,” covering 17,000 hectares, was established in the Kazakh steppe. Under this name emerged an institution that, from 1931 to 1959, shattered the lives of six million political prisoners, deportees, and prisoners of war. The name of this blood-soaked monster is Karlag of the NKVD.

A memorial cross stands at the Spassk cemetery of Camp No. 99, 25 kilometers from Karaganda. Here, political prisoners and internees were held in inhumane conditions, and beginning in 1941, prisoners of war as well. According to official records, more than five thousand of them remained forever in this mass grave.

There is no place here for oblivion or lies. It is deafeningly quiet. And terrifying. Kazakhs, Germans, Russians, Romanians, Hungarians, Poles, Belarusians, Jews, Chechens, Ingush, French, Georgians, Italians, Kyrgyz, Ukrainians, Japanese, Finns, Lithuanians, Latvians, Estonians — the infernal millstones of the NKVD ground everyone without distinction. The eerie silence is broken only occasionally by the chime of the memorial bell.

The Karlag system included numerous camps and special-regime zones. The largest were Spasslag (prisoners of war), ALZHIR (the camp for wives of “traitors to the Motherland”), and Steplag (Ukrainians, Baltic peoples, Vlasovites). The administrative center of Karlag was the village of Dolinka, located 50 kilometers from Karaganda. The total territory of Karlag was comparable to that of France. After the closure of Spasslag, nearly all buildings were destroyed. A military unit was placed on the site of the camp administration.

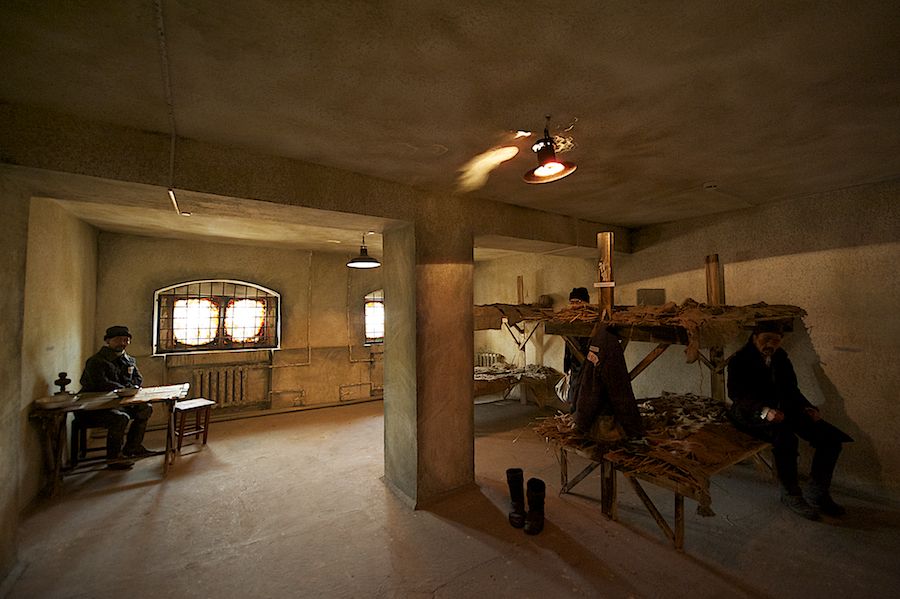

The primary activity of the prisoners was quarrying stone for the construction of roads. All work was done manually. People died from cold, hunger, and physical exhaustion. The weakest were finished off by the guards.

The walls were built to last for centuries. Stones were fitted with absolute precision, without gaps and without mortar. Those who died during construction were simply buried beneath the foundations, and the work continued.

When the camps were established, NKVD special units forcibly evicted all local residents from the territory. Livestock was often confiscated. For Kazakhs, this meant certain death from starvation.

All of Dolinka was wrapped in barbed wire. Entry was permitted only with a special pass, a rule that remained in effect until the early 1980s. Several functioning colonies still surround the settlement. After the camp was dismantled, only scattered coils of barbed wire remained in the steppe. Even scrap collectors avoid these “hedgehogs.”

A grand building in the style of Stalinist Empire. The center of hell. The Karlag administration in Dolinka.

Today it houses a museum of victims of political repression.

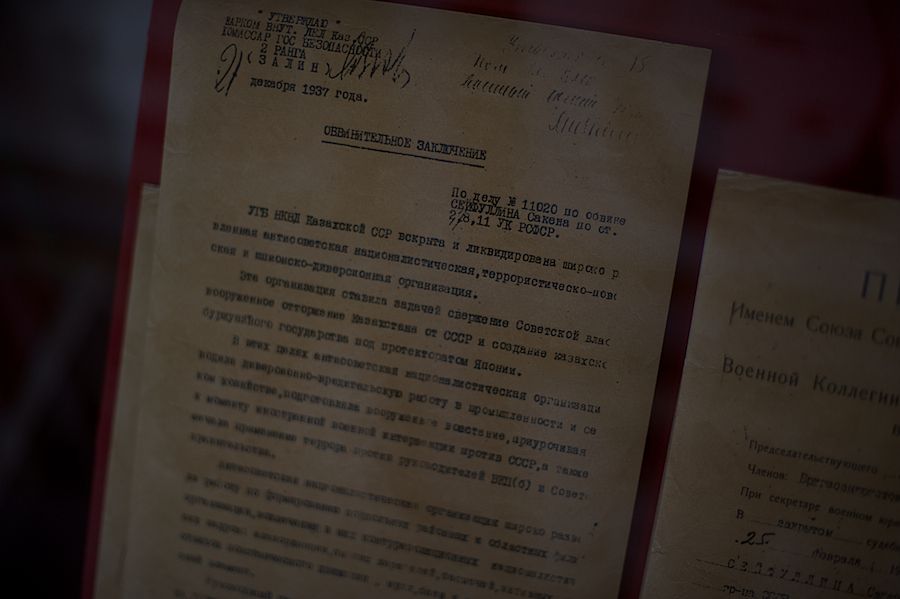

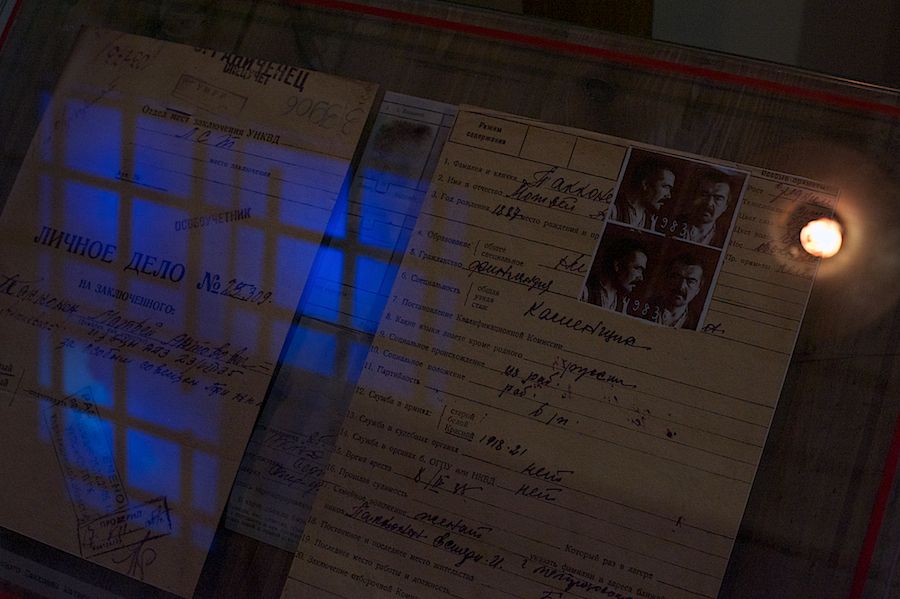

Under the glass lie original documents — living evidence of a ruthless system whose purpose was to turn its own people into a faceless mass of slaves.

The indictment of Saken Seifullin. The great writer and patriot of his homeland was arrested as a “bourgeois nationalist working for Japanese intelligence” and executed on February 28, 1939, in the Alma-Ata NKVD prison.

Under false accusations, all leaders of Alash-Orda were destroyed in the torture chambers of the NKVD. Thus the Stalinist machine annihilated the Kazakh intelligentsia that struggled for Kazakhstan’s independence after the Revolution.

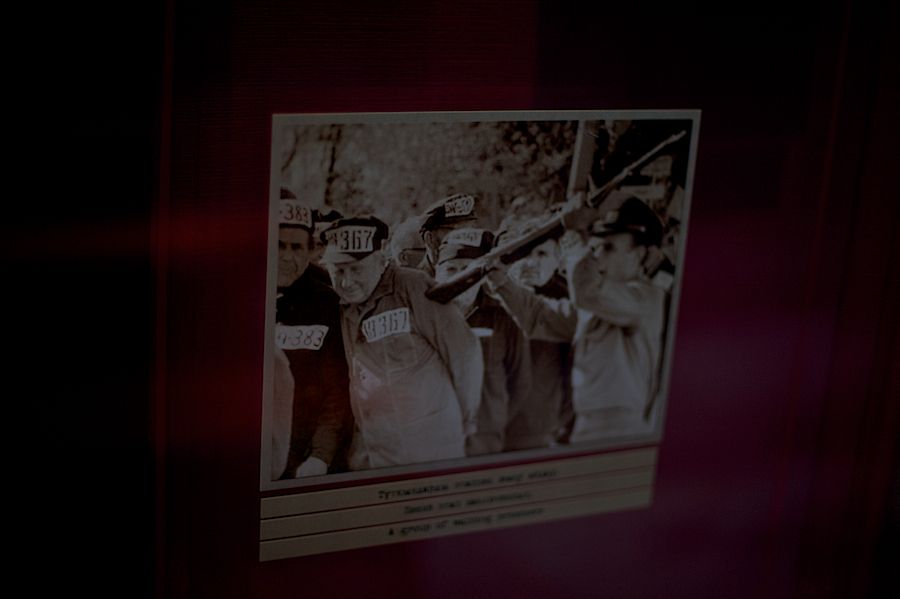

Karlag guards were recruited from “class-appropriate elements” — people without principles, obedient and cruel. To earn a bonus, guards killed two prisoners and reported to the leadership that they had prevented a mass escape. Bonuses for “mass escapes” were twice as high as for single escape attempts.

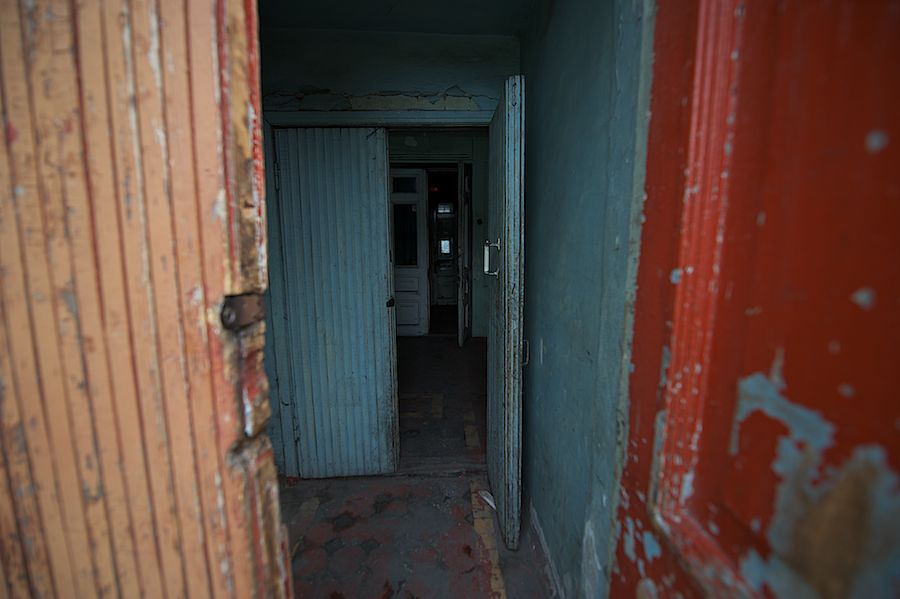

The basement corridor. The torture chambers, isolation cells, and execution wall were located here.

Most political prisoners fell into the hands of the NKVD due to anonymous denunciations.

Behind these doors, the lives of hundreds of innocent people were shattered.

The isolation cell. A prisoner was allowed to sleep on the icy floor only four hours a day. The rest of the time he had to stand. Any attempt to lean on the wall was punished by merciless beatings.

The most defiant were placed into a pit and denied food and water for days.

Several “sharashka” laboratories operated in Karlag — scientific workshops where imprisoned scholars were forced to work “for the good of the Motherland.”

No record was kept of those who died from disease, and their personal files were destroyed after death. Thus a person disappeared forever.

Intellectuals from across the Soviet Union were exiled to Karlag, including such figures as the great biologist Chizhevsky, Lev Gumilev, and Father Sevastian.

Interrogations were conducted around the clock. Many people lost their sanity.

For NKVD personnel, this was ordinary work, unquestioning execution of orders from above.

Propaganda in the camps was organized at a high level.

A torture chamber. The smell of blood still lingers here. People were beaten, tortured with electricity, their fingers crushed with hammers.

The execution site at the end of the basement corridor. Here the “highest measure of social protection” — the death penalty — was carried out. The condemned were ordered to stand facing the wall. The guard fired a shot into the back of the head through a grate.

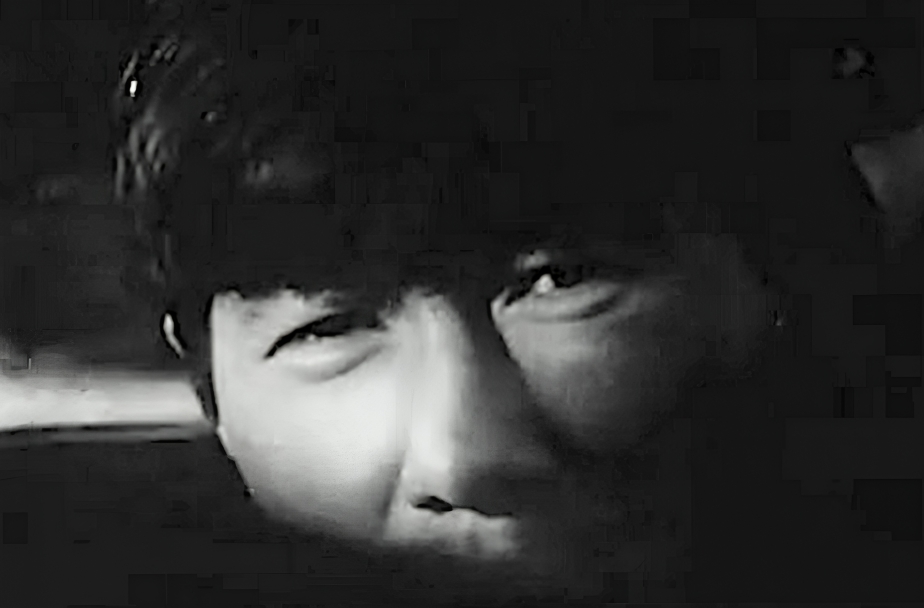

Ivan Ivanovich Karpinsky, a participant of the Kengir uprising, was a prisoner of Steplag.

— I am from Ukraine. I was arrested for reading “bourgeois literature.” It was simply a book on the history of Ukraine. For that I was sentenced to 25 years in the camps. And I was only 19... That is how I ended up in the Kengir settlement, where prisoners were building Zhezkazgan. Most of them were young men from Ukraine, the Baltic states, and Vlasovites.

— The guards were brutal. Prisoners were killed for no reason. On Easter, the guards opened fire on a column of inmates. The next day, the entire camp refused to go to work. To “teach us a lesson,” criminals — “urki” — were brought in. They were supposed to kill us. But we did not allow it. Fifteen people died in that massacre. That was the breaking point...

— On May 16, 1954, we barricaded the camp and demanded changes to the camp regime. For 42 days we held our ground. And on June 26, several explosive bombs were dropped on us from an airplane. Then tanks entered the camp. They fired at the barracks, crushed people beneath their tracks. The earth was soaked with blood. Neither children nor women were spared.

When asked, “How did you survive?”, Ivan Ivanovich cried…

— They took us away to be killed in ore wagons. They planned to throw us into a mine shaft. For fifteen minutes we hung over a 40-meter abyss. One push of a button — and we would have been dead. But at the last moment they changed their decision. And that is how I survived...

— Here I am with my cellmates in 1954. The heavy memories still haunt me, and I cannot erase from my mind those four years of true hell.

The living conditions of women were no different from those of men. The same filth. The same hunger. The same hopelessness.

There was only one “advantage” — women were rarely executed.

Polina Petrovna Ostapchuk, a former Karlag prisoner.

— I am from Ukraine. After the war, we lived in terrible hunger, and I collected money for the post-war state loan. Fifty rubles each — a huge sum at the time. I stood up for a widow with four children so that they would not take her money. For that, I was sentenced to ten years. They added accusations of “working for American intelligence.” They did not let me sleep for a week, and I signed everything.

— In 1948, I was sent to Spassk. I spent four years there. I survived by miracle. Then came Aktas. Construction in summer, factory in winter. Four years with a jackhammer. I was released only in 1956, after serving eight years.

— When I was young, I was a pretty girl, and the camp commandant began courting me. For four months he followed me, but I refused him. Then he threatened to arrange a “tram” — when eleven men rape you, and the twelfth is infected with syphilis. One girl was infected this way and soon died. I had to agree to save my life. That is how I lost my virginity in the camp and gave birth to my first son...

During her imprisonment, Polina Petrovna observed an artist painting and secretly learned to draw herself.

Polina Petrovna shows a drawing of her place of imprisonment, recreated from memory.

— Many people died. In Spassk, five coffins a day were taken out of our unit. The coffins were light — that is how exhausted the people were. And there was complete lawlessness. Women were raped, people were tortured. But, thank God, all that is now in the past.

— I also write poetry. It is an emotional refuge for me. I learned it in the camp’s arts circle. I also sang. We traveled to other camps with concerts. I served the final years in Dolinka — we built houses there and gave performances.

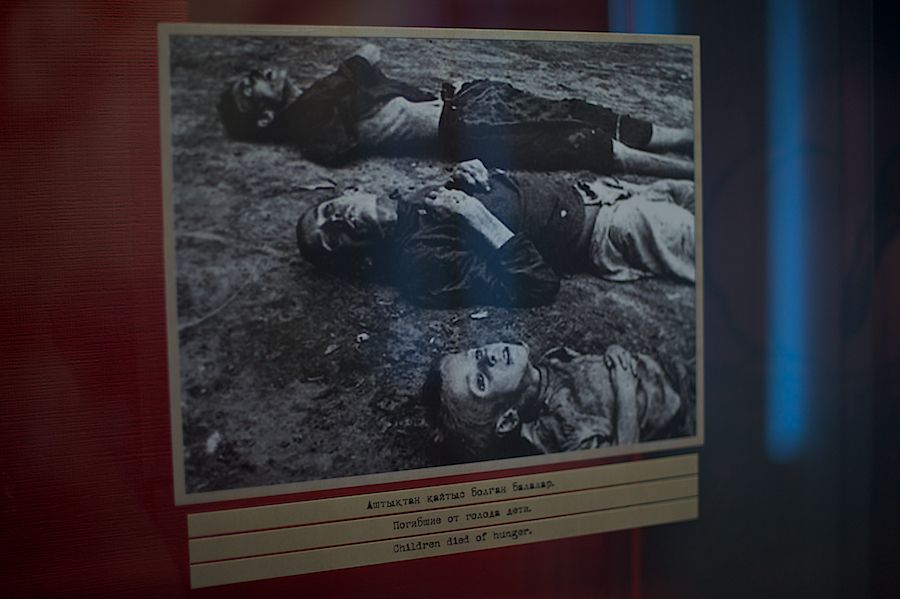

Women lived through unbearable hardship, separated from their children. And the children themselves suffered the full cruelty of the regime and silently carried the stigma of “children of enemies of the people.”

A crib from the Dolinka orphanage. As soon as a child grew older, they were taken away to the orphanage. Many never saw their mothers again.

The caregivers constantly reminded the children who they were.

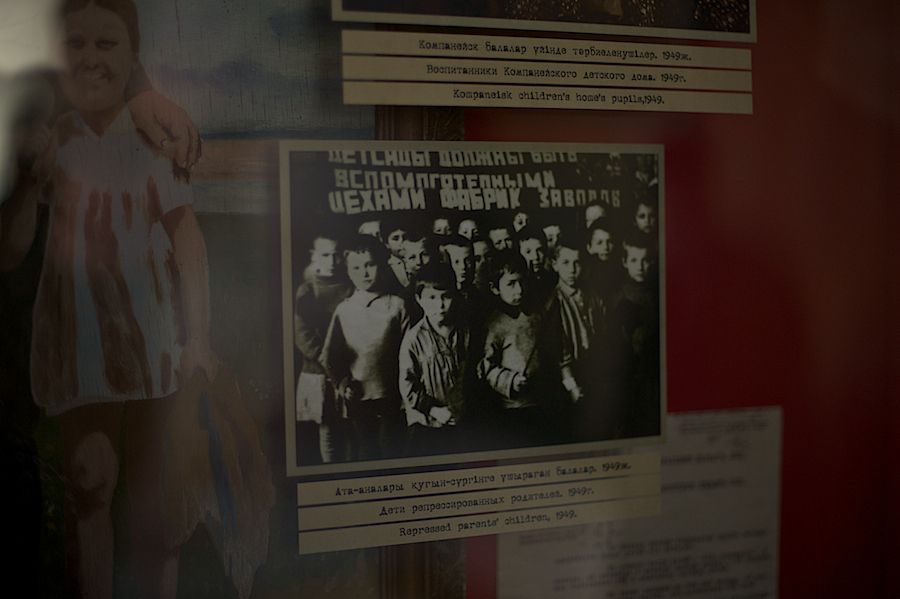

The children were dispersed to orphanages throughout the Soviet Union. Their names and surnames were often changed.

Zoya Mikhailovna Slyudova — a child of Karlag.

— My mother was exiled from Belarus in 1939, she was only 18. I was born in 1940 and grew up in Dolinka. Our caregivers were “wives of traitors to the Motherland.” At age eight, we were moved to the Kompaneisky orphanage. The caregivers took our bread. There was no heating in winter. We, the children, carried out our dead. Many died. They buried children in wooden barrels. No coffins were allotted for them. We were the children of enemies of the people — no one pitied us...

— I never saw my mother. According to the documents, she was executed somewhere near Krasnoyarsk. In 1955...

Children died of hunger every day. Grief never left this cursed place for a single moment.

Children born and deceased in the camp were buried here. In reality, the burial grounds were much larger.

A vast children's cemetery the size of twenty stadiums.

These barracks — built by prisoners — housed the camp guards. Some of them have since been dismantled for bricks. Others are still inhabited by descendants of former prisoners.

Sergey, head of a farming household. His father spent 18 years in the camps:

— In the mid-1970s, the state farm decided to deepen the dam. A bulldozer removed half a meter of soil and stopped. The ground was completely white with bones. Most of the skulls were children’s. To avoid scandal, everything was quickly buried again.

The hospital complex of the Dolinka NKVD administration.

Yura, the hospital guard. His mother was a repatriated Volga German.

— Everything here is preserved exactly as it was during Karlag.

The hospital is still functioning and serves the local population.

The corridor resembles wartime.

— During Karlag times this was a canteen, — says Yura. — Now it is the boiler room.

All victories and achievements, all historic constructions, mines, roads, and factories that were proudly celebrated by Soviet authorities were built with their blood and sweat. With their lives. With their broken destinies. With the tragedies of entire nations and of every individual. We have no right to forget this...

The original version of this material was published on Voxpopuli.kz (before its closure in 2023). The author restored the text and photographs from a personal archive to preserve documentary and historical materials.

О ветеранах Великой Отечественной войны — истории мужества, подвига и памяти поколений. Фоторепортаж Карлыгаш Нуржан для Shanger.kz.

A detailed account of the 1986 December protest in Almaty and the people whose lives were forever changed. Photo story for Shanger.kz

Witness accounts and hidden history of Kazakhstan’s 1986 December protests...Фоторепортаж Карлыгаш Нуржан для Shanger.kz ....

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!