Kazakhs of Mongolia: In the Steps of Chinggis Khan

VoxPopuli and Karla Nur

Let us recall that in the previous photo report the participants of the “In the Footsteps of Chinggis Khan” project started out from Almaty and, having reached the Altai Republic (Russia), stopped in the village of Kosh-Agach, where they gave a musical concert. That same evening the entire team received a surprise: the return of the Dutchman Robert Ermers, who was overjoyed to be back among the travelers. The next morning the group sets off toward the Mongolian border. In the photo, Turkologist Napil Bazylkhan points on the map to the northern road, which is rich in ancient monuments.

From the Russian village of Kosh-Agach to the border village of Tashanta is 45 kilometers. At the border they had to wait for several hours.

While the formalities with documents were being settled, the group got acquainted with bikers from Poland.

Not far from there, long-haul truck driver Mikhail had parked his truck; he was hauling bitumen for road construction in Mongolia. As practice later showed, people like Mikhail are the most welcome people in this country.

Near the Mongolian border post there is a small hotel where one can get a meal. By that time everyone was very hungry, and home-style food would have been just right.

But each person received only 2–3 manti and a cup of tea. However, the real surprise was the bill presented by the hotel owner — about 400 dollars for lunch.

Organizer Bakhytgul: “We had to bargain it down to 120,000 tugriks (12,000 tenge). Next time we’ll order from a menu with prices.”

Across the entire territory of Mongolia only about 5% of the roads are paved; all the rest are dirt roads. Driving on them is pure torment.

At last the appearance of an asphalt road signals that the city of Bayan-Ölgii is near.

The brightly colored vehicles with the Kazakh flag catch people’s eyes, and many stop to get acquainted. Mullah Kuandyk with his family. His daughters speak only Kazakh.

On the horizon the long-awaited city appears.

Singer Asem: “I’m a little anxious about how the Kazakhs here will receive us,” she says.

Unusual motorcycle taxis can take you anywhere in Mongolia, at a price of 400 tugriks per kilometer (about 40 tenge).

Mobile network advertising.

Vultures here play the role that crows play elsewhere.

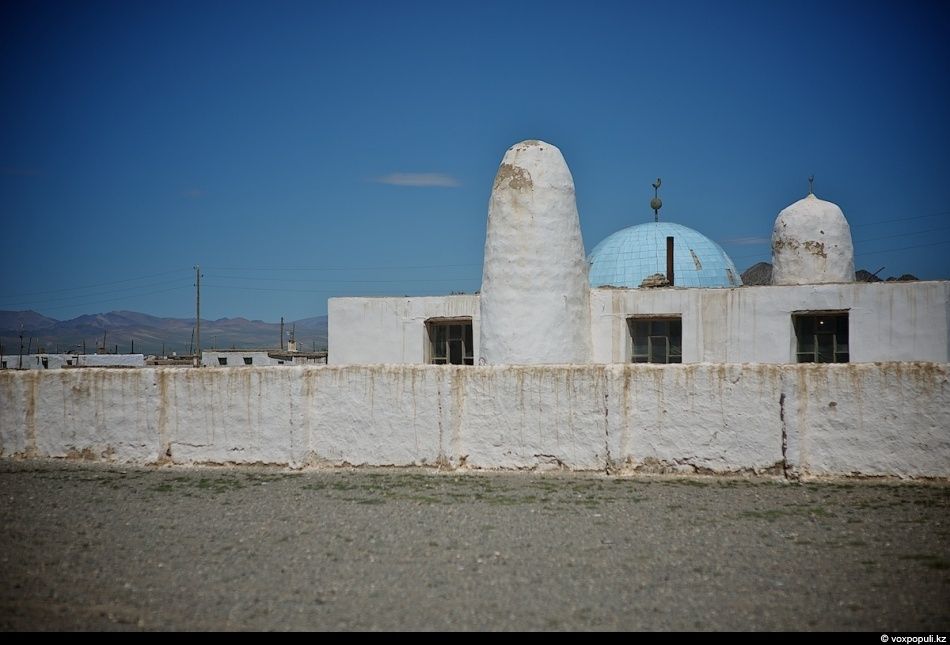

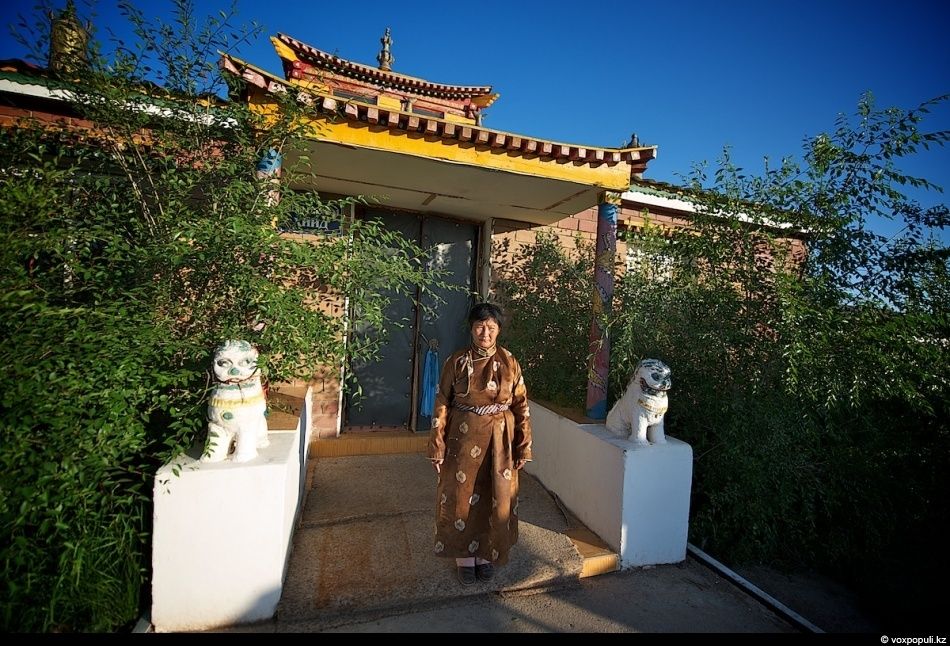

The Kazakhs of Mongolia mostly practice Islam, but there are also those who follow Buddhism.

Mullah Abdulla.

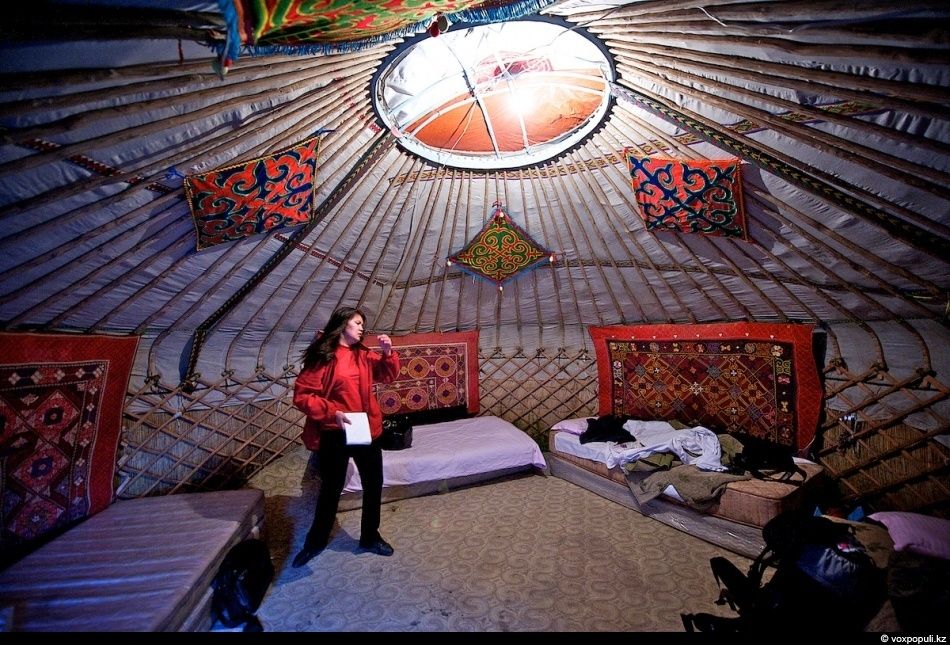

Almost every yard has one or two yurts standing in it.

For the night the participants stopped at an ethnic hotel, where instead of ordinary rooms guests are lodged in yurts. Inside the yurt there is everything necessary: beds, chairs, a table, electricity, a stove, and even WiFi. The shower, toilet, and bathhouse are located in a separate building.

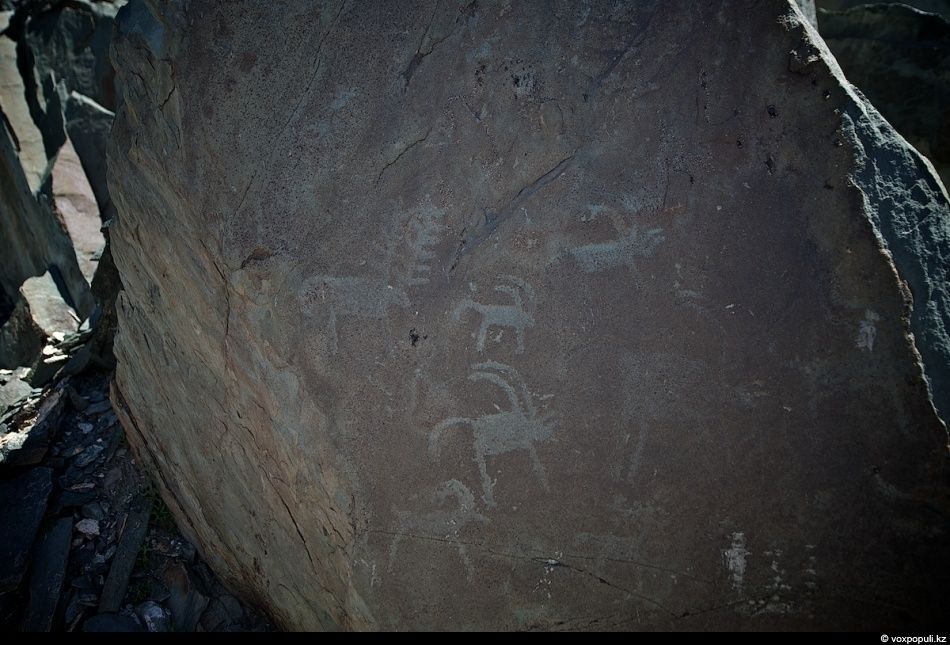

Drawings on deer stones.

Фото Бауыржана Булатханова

Stone statues “Baga khargai”, 8th–9th centuries. Mongolia, Bayan-Ölgii aimag, Sagsai.

The total number of ethnic Kazakhs in Mongolia is more than 140,000 people, which is about 5% of the country’s population. Of these, about 90,000 live in Bayan-Ölgii aimag; they are divided into two clans: Abak Kerei and Naiman. A woman explains: “We are from the Abak Kerei clan, the indigenous people of these lands. We devoted our whole life to animal husbandry; it is the only source of income for our family.”

In summer people live in yurts, and in the cold months they return to their winter camps. There are Kazakh schools in Mongolia, but the mother tongue is mostly taught within the family.

Sholpan shows the wooden baby cradle, the “besik”, of her youngest son.

The drink with which Sholpan treats guests is called hot kurt. It is considered a remedy for colds and tuberculosis.

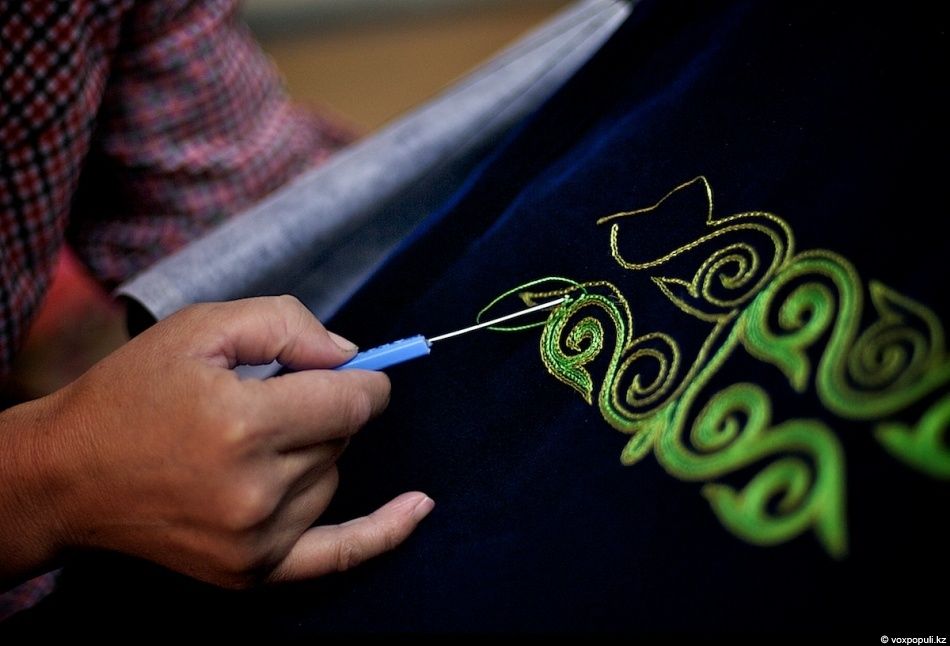

“Altai Kerei” Hand Craft is a small shop of national Kazakh items made in the nomadic tradition. Prices range from 3,000 to 45,000 tenge.

On the second floor of the shop there is a workshop.

All seams and stitches are made by hand. One quilt can take several months of painstaking work.

Over six years of operation, the shop has built a reputation for quality products. Tourists from England, Turkey, and Japan are especially fond of their items. The “Altai Kerei” team often travels to Kazakhstan, taking part in exhibitions and competitions.

Фото Бауыржана Булатханова

At that time the annual Mongolian national holiday Naadam was underway in the country. It consists of three sports: archery, horse racing, and wrestling. Mongolian national wrestling is called “bökh”. Before the competition, all the wrestlers come out to the center of the field and, waving their arms like wings, perform a dance that imitates the flight of a proud bird. This dance symbolizes strength and pride. At the end of the tournament, only the winners perform this dance. The wrestlers’ outfit includes boots, shorts, and a short jacket with long sleeves but an open chest.

Фото Бауыржана Булатханова

The wrestlers’ open costume is explained by an old Mongolian legend, which tells of a woman disguised as a man who once defeated the strongest wrestler. She beat everyone who challenged her, and thus all the mightiest champions were laid low. When the men discovered that they had been defeated by an ordinary woman, it became a great shame for them. From that time on, in order to avoid such disgrace and to prevent women from taking part in the competition, it was decided that wrestlers’ chests must be left bare.

Фото Бауыржана Булатханова

Under the rules of the sport, a wrestler is considered defeated if he touches the ground, for example, with an elbow or knee. A folk dictum says, “You must not disturb the earth.” Mongolian wrestlers are considered among the strongest in the world. For example, in Japan there are 33 Mongolian sumo wrestlers who live and compete on the tatami.

Фото Бауыржана Булатханова

A Kazakh eagle hunter at the Naadam national holiday.

Because the convoy was one day behind schedule, instead of the northern road they had to move along the southern one. This road is less interesting, but shorter and safer. Thirty-seven kilometers from Bayan-Ölgii, among the rocky cliffs, the lake Tolbo-Nuur appears before the participants.

Along the way the group is forced to stop several times because of punctured tires. Organizer Bauyrzhan Bulatkhanov says: “Over the entire trip we had only five punctures in our group. Considering the roads of Mongolia, where stones are as sharp as a knife’s edge, five punctures are nothing. Good tires really did not let us down.”

Approach to the city of Khovd.

Here they make a short stop to change punctured tires and refuel.

A Buddhist temple in the village of Darvi; the group sets up camp for the night next to it.

In the morning — the town of Altai.

A stone statue “Dengiyn süm”, 8th–9th centuries, near the local history museum in the town of Altai.

On the high mountain plateau between the settlements of Altai and Bayankhongor, the convoy of vehicles suddenly lost sight of one another and split off in different directions. This was the most frightening moment of the entire expedition: finding yourself alone in an unfamiliar steppe, with not a soul for many, many kilometers around, was truly eerie. An hour and a half passed before all the participants reunited again.

Photographer Rustem Rakhimzhan: “When they told me what had happened, I had only just woken up and was sitting in the car with a square head,” he jokes.

Musician Abulkhair Abdrashev hugs his father when they meet: “I was so overwhelmed with emotion that I simply told him how much I love him.”

“There were several reasons for the convoy breaking up,” Bauyrzhan explains. “First, the huge number of branching roads. Second, the dust, which blocks the view so you can’t see the vehicles behind you. And third, the drivers’ lack of experience in convoy driving.”

“Just that morning I had said that each of us had grown a little and learned to work more in sync as a team, and then suddenly everyone behaved like children, starting to play racing games. But I’m glad that we all found each other, everyone is safe and the vehicles are in good condition. Still, I worried that with such an attitude we were risking not reaching Ulaanbaatar at all.”

Tired and exhausted by the road, the participants reach a small settlement and decide to set up camp nearby.

Before darkness falls, they need to have time to pitch the tents and prepare dinner.

The closer they get to Ulaanbaatar, the more colorful the taxi drivers become.

Mongolia is world-famous for its wool processing. The cashmere produced here is highly popular in countries such as Italy, France, England, and Russia.

Raw goat milk is considered less dangerous than cow’s milk, because goats are more resistant to disease. Brined cheeses, including bryndza, are made from goat’s milk.

This was the last stop before the third stage of the journey. Only by early morning would the convoy arrive in the homeland of the great military leader Kültegin, but about this and other adventures of the “In the Footsteps of Chinggis Khan” project you will be able to read in the final photo report “Great Mongolia”.

The original version of this material was published on the Voxpopuli.kz portal (before its closure in 2023). Author Karlygash Nurzhan restored the text and photos from her personal archive to preserve documentary and historical materials.

A 15-day journey through Karakorum, Kül Tegin’s monument, and the legacy of Great Mongolia. Photo essay by Karlygash Nurzhan for Shanger.kz

Экспедиция «По пути Чингисхана» по Алтайскому краю — древние города, курганы и память кочевой культуры. Фоторепортаж Карлыгаш Нуржан для Shanger.kz.

The Kazakh diaspora in Turkey: migration history, daily life, traditions and human stories… Фоторепортаж Карлыгаш Нуржан для Shanger.kz

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!