Guardian of the Bokey Legacy: 30 Years of Protecting History

Shanger.kz and Карлыгаш Нуржан

Sholpanai Amanzholova is often called a living encyclopedia of the Bokey Horde. Historians, local researchers, and descendants of the famous dynasty regularly turn to her for guidance. In her small apartment in Almaty, she preserves a unique archive unmatched by any museum in Kazakhstan. Dozens of old photographs, documents, and letters — some inherited, others carefully collected and systematized over three decades. Our correspondent met with the researcher to learn how she exposed fake portraits of Khan Zhangir, found the grave of Shangeray Bokey, and reconstructed the genealogy of the renowned Bokey dynasty.

Sofya Bokeykhan, a 2nd-grade student of the gymnasium.

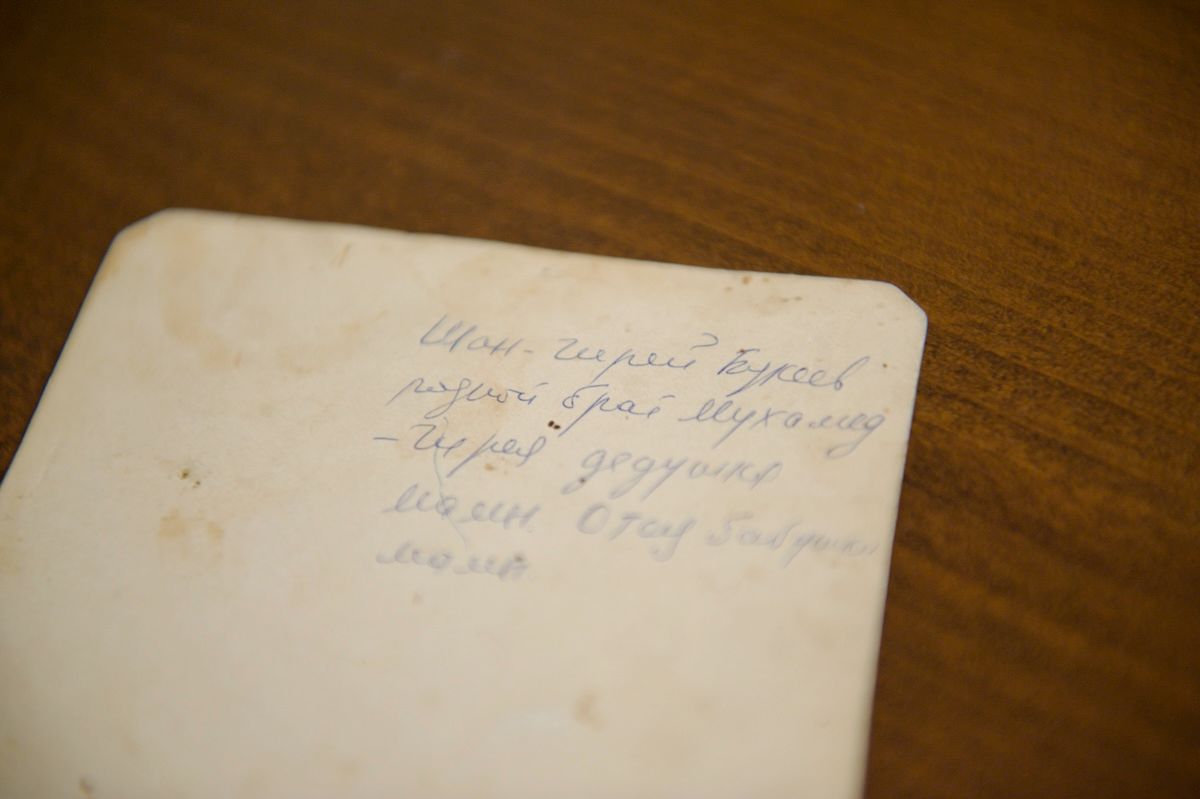

On her mother’s side, Sholpanai is a descendant of Mukhametgeray Bokey, the elder brother of the famous Shangeray Bokey. Her grandmother, Sofya Dauletovna Bokeykhan, a great-granddaughter of Khan Zhangir, often told her granddaughter captivating stories about their ancestors — about Khan Zhangir, his descendants, and the Bokey dynasty. Little Sholpanai found these stories hard to believe, but it was exactly those childhood impressions and the carefully preserved family relics that sparked her interest in the history of her lineage.

Adopted daughter of Shangeray, Zaureş Bokey (second from left).

The unique photo archive was passed down to Sholpanai by two heroic women — her grandmother Sofya and Zaureş Mukhametgaliyevna Bokey. During the years of repression, when family photographs were being destroyed en masse and any connection with “enemies of the people” could lead to arrest, these women risked their lives to preserve the memory of the dynasty. Sholpanai’s own contribution lies in identifying the people in the photographs, reconstructing their destinies and the forgotten chapters of the Bokey Horde’s history, turning anonymous images into a documented narrative.

Sholpanai Amanzholova became a regular participant of academic conferences; she was invited to Uralsk, Saratov, Orenburg, Samara — everywhere traces of the Bokey Horde remained. Museums of Western Kazakhstan, archives across Russia — all these institutions know her as a tireless researcher who can spend hours working with documents, carefully piecing together the history of her family. Her articles are published in scientific journals, and she consults authors of books and encyclopedias. In 2018, it was Sholpanai Amanzholova who submitted the biographies of 18 descendants of the dynasty for the Encyclopedia of Kazakhstan — among them members of the State Duma, figures of the Alash Orda movement, doctors, and public intellectuals.

From the personal archive of Sholpanai Amanzholova

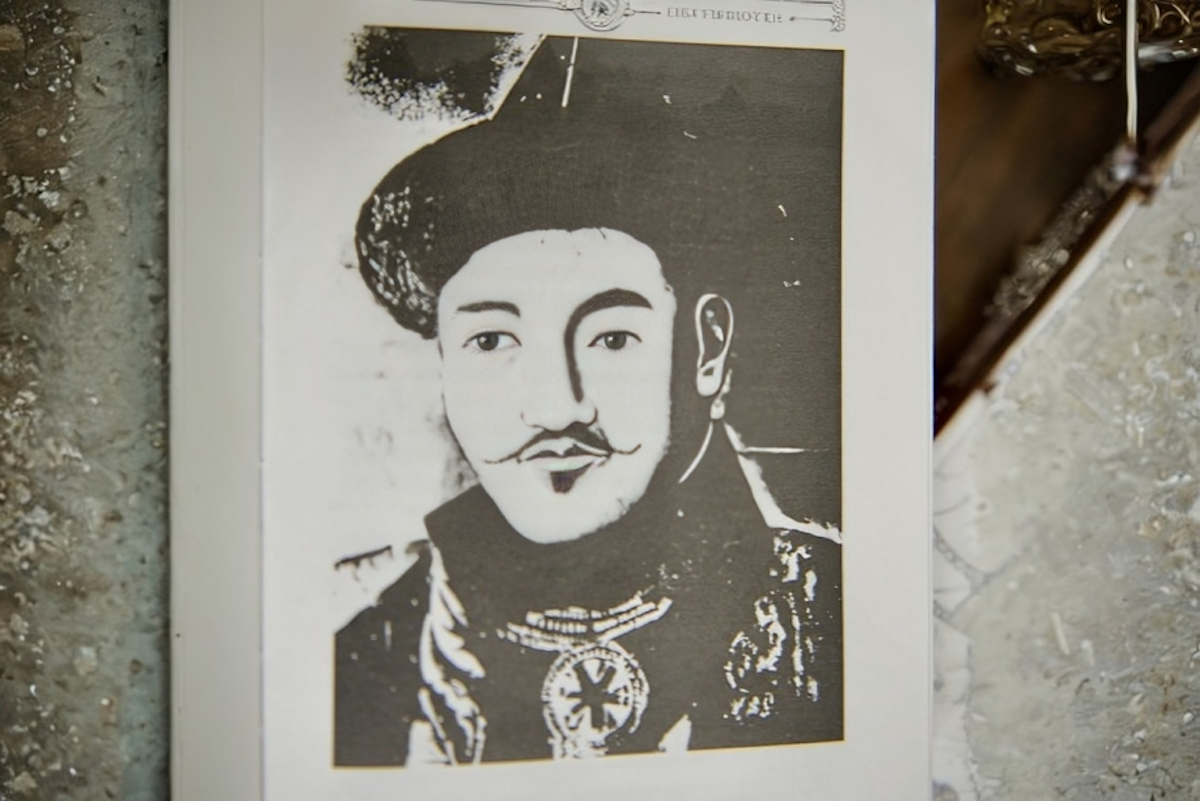

“One of the most important results of my work was exposing the fake images of Khan Zhangir that had been circulating for decades in museums, publications, and even remain on Wikipedia to this day,” Sholpanai explains. “I discovered that historiography contained various portraits of entirely different people, yet they were presented as portraits of Khan Zhangir. For example, in the Bokey Horde Museum in Uralsk, there was a photograph of a man with clearly Mongoloid facial features, while another photo showed someone who looked more Persian. Two photographs from my own archive are especially telling — they were long mistaken for images of the Khan.”

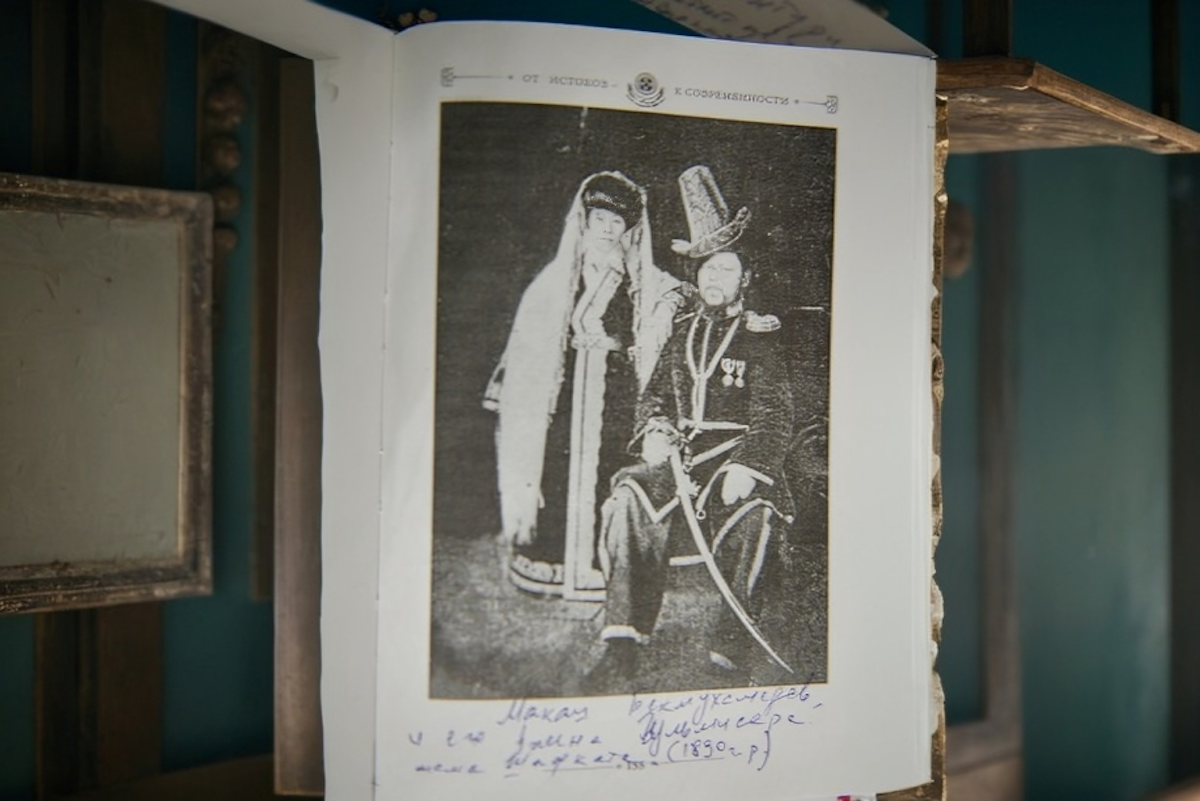

In the photo: Makash Bekmukhamedov and his wife Gulsara, 1890.

“In the first photograph, a man is dressed in an elaborate ceremonial outfit with a high ornamented headdress and medals on his chest, standing beside a woman in traditional embroidered clothing. The photo is dated 1890 — forty-five years after Khan Zhangir’s death.”

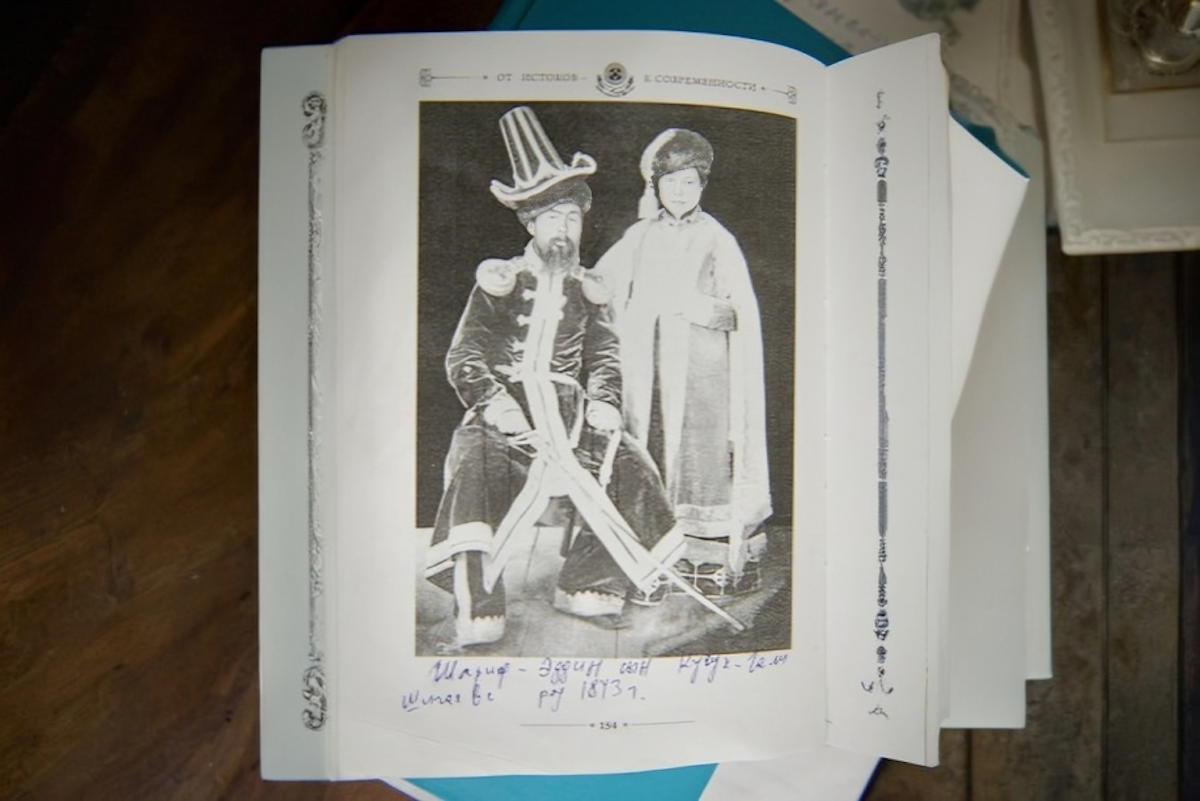

In the photo: Sharif-Eddin, son of Kushik-Ali, with his wife, 1843 (this photograph is still incorrectly presented on Wikipedia as a portrait of Khan Zhangir)

“The second photograph, dated 1843, shows a man with his wife, both wearing traditional attire. The man is holding a saber. These images cannot possibly depict Zhangir, if only because the daguerreotype — the world’s first photographic technique — was invented in 1839 in France, and it took years before it reached the remote steppes of the Bokey Horde.”

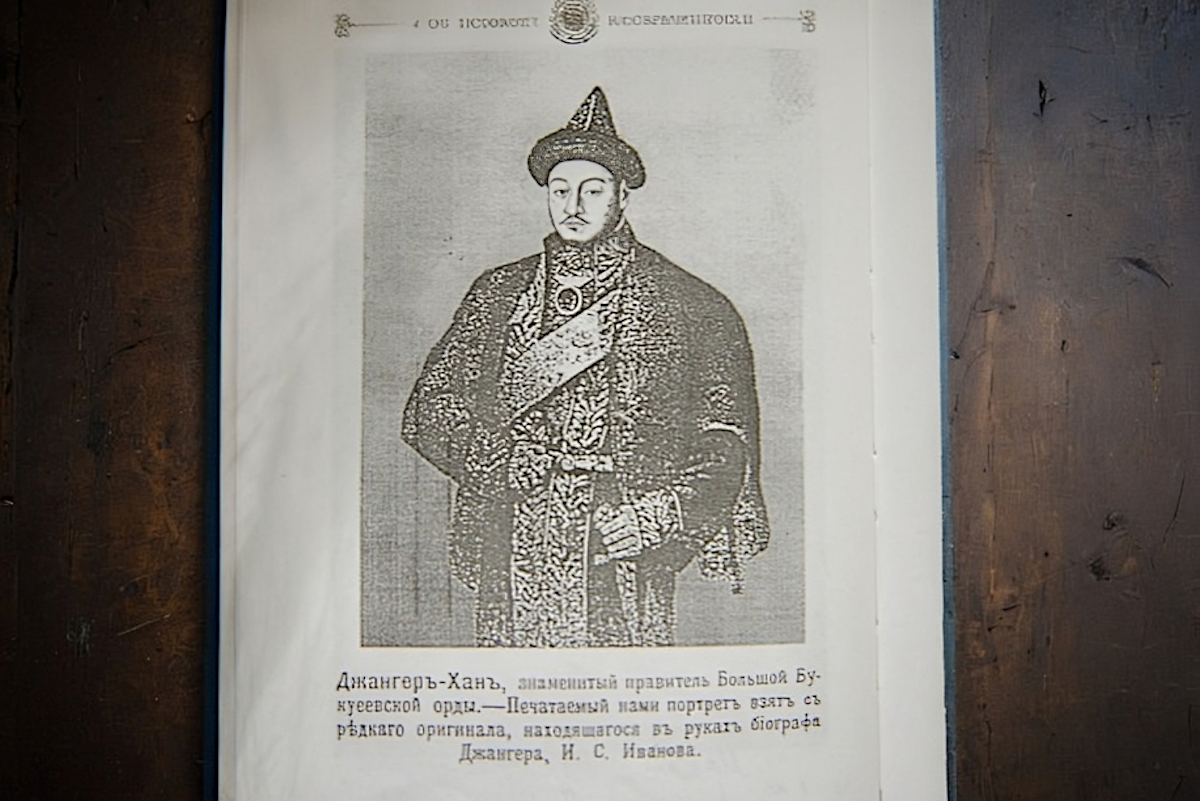

“I began a meticulous study of all available descriptions of the Khan’s appearance left by his contemporaries. In 1826, Professor K. F. Fuks of Kazan University described Zhangir as a man of European facial type — fair-skinned, with prominent grey or blue eyes, a short beard, medium height, and a sturdy build. I established that the Khan resembled his mother and had characteristically slightly protruding eyes. Comparing these descriptions with preserved portraits from Kazan University, where Zhangir was an honorary member, as well as with the portrait published in the book by his first biographer, I. S. Ivanov (included in the archival volume History of the Bokey Horde, compiled by Bulat Zhanaev and Vyacheslav Sinochkin), I proved that the images displayed in the Uralsk museum have nothing to do with the real appearance of the ruler. The portrait documented by Ivanov is the first authentic depiction of Khan Zhangir. Even now, fake photographs continue to circulate online, and I continue the fight for historical truth by providing museums and journalists with copies of the genuine images from my archive.”

Janger-Khan, the renowned ruler of the Great Bukey Horde. The portrait published here is taken from a rare original held by Janger’s biographer, I. S. Ivanov.

“Khan Zhangir ruled the Bukey Horde from 1823 to 1845 and entered history as an enlightener and reformer. He was the first to understand that the era of nomadic civilizations was irreversibly fading, and he actively promoted the adoption of European cultural advancements while preserving Kazakh national identity. Under his rule, the first secular school appeared, the first pharmacy, smallpox vaccination was introduced, mosques were built, a major fair was established, and agriculture and early industry began to develop. In 1840, for his contribution to education, Zhangir Bokey was elected an honorary member of Kazan University, and the following year he was awarded the rank of Major General.

His wife, Fatima — daughter of the Orenburg mufti and Russian diplomat Mukhametzhan Guseinov — not only supported her husband but initiated many projects herself. Her education, beauty, and refined manners opened the doors of elite salons in Orenburg, Ufa, the Volga region, Moscow, and St. Petersburg to the ruling couple.”

“A special place in my research is occupied by the figure of Shangeray Bokey, the grandson of Khan Zhangir. Alihan Bokeykhan, by virtue of seniority and respect for his merits, invited him to join the Alash party and sent special envoys to him, yet Shangeray never became a member. Unlike his brother Mukhametgeray, a Sufi and deeply religious man, Shangeray led a secular life. He owned a model estate with advanced farming methods, engaged in science and technology, and invited engineers to work with him. Shangeray transformed his estate, Kolborsy, on the banks of the Torgyn River near the German village of Savinka, into an intellectual center of the entire region. His home was called the “Mecca of the Kazakh people,” compared to Tolstoy’s Yasnaya Polyana, and became a gathering place for poets, intellectuals, and public figures.”

Sholpanai holds in her hands the original photograph depicting Shangeray Bokey.

“In all early photographs, Shangeray is dressed richly, wearing a bow tie, appearing every bit the sophisticated, worldly gentleman. But in the second half of his life, he transformed — his clothing became markedly more ascetic.”

“A tragedy befell him in January 1920,” Sholpanai continues. “During the civil war, fleeing from the pursuit of Cossacks in blue hats — presumably Orenburg Cossacks — Shangeray’s family fled toward Zhambyt. To divert the pursuit away from his loved ones, Shangeray and his son Bakash led the Cossacks in a different direction. The family managed to escape, but Shangeray and his son did not. Shangeray died of his wounds and exhaustion, without regaining consciousness, lying on a bundle of hay in the severe frosts of early January 1920, in the area of Akbakay. His son died the next day. They were buried by Lukpan Mukhitov, a relative on his wife’s side. The location of their graves remained lost for decades.”

The estate of Shangeray Bokey. Borsy, Ural region. 1905. Original photograph by Shangeray Bokey.

“One of the most emotional episodes of my research work was my 1995 trip to the Bokey Horde,” Sholpanai recalls. “After the dispossession of 1928, our family never returned to its historical homeland — nearly 70 years had passed. I understood that I was traveling to a place where no one knew me, where I barely spoke Kazakh and knew little about local customs. So I decided not to arrive empty-handed. I brought with me a stack of my research — 16 kilograms of archival materials I had collected about the Bokey Horde — and I was welcomed with open arms.

At that time, Bolat Zhanaev, Director of the Kazakh State Archive and co-compiler (with V. Sinochkin) of the unique document collection History of the Bokey Horde, helped arrange meetings with local intellectuals. The presentation of the book happened to be taking place then, and I was publicly thanked for my advice and consultations. One of the meetings was attended by Krymbek Kusherbayev, then Akim of the West Kazakhstan Region. When I told him that I wanted to find the burial place of Shangeray Bokey, he immediately organized an expedition. To my surprise, construction of a mausoleum had already been underway since March.

The head of the construction team wondered why no descendants had come to visit such a notable man. When I saw the white shroud containing Shangeray’s remains being carried into the new mausoleum, I fell to my knees and said: ‘If Khan Zhangir and the Almighty recognize me, I am ready to take responsibility for all those who could not come.’ From that day on, I felt a special responsibility for preserving the memory of the dynasty.”

Visiting the home of Shangeray Bokey. First row, left to right: Aisha Kusaypgaliyeva, daughter of Mukhamedgeray; Gainnizhamal, daughter of Aisha and wife of I. E. Zarubin; doctors Zarubin and Kashin — colleagues of Kusaypgaliyev. Second row, right to left: Imangali — Sh. Bokey’s secretary; Dauletshakh Kusaypgaliyev — father of S. Bokeykhan; Mukhametgeray Bokey and his son Akysh Bokey. In front of Shangeray Bokey’s house in Borsy, Ural region. Original photograph by Shangeray Bokey, 1905.

“The uniqueness of my archive lies in the fact that many of the photographs exist only in a single copy — in my collection,” Sholpanai explains. “The photographs of the 19th–20th centuries depict members of the Bokey dynasty, figures of the Alash Orda movement, relatives, and family friends. Especially valuable are the photographs of Shangeray’s estate on the banks of the Torgyn River: they show the family, their daily life, clothing, and the architecture of the manor. In many images you can see Mukhametgeray Bokey, Shangeray’s brother. There are very few photos of Shangeray himself — he was a passionate photographer and often stayed behind the camera.”

Original photograph by Shangeray Bokey.

“My grandmother Sofya never explained in detail who was depicted in the photographs,” Sholpanai recalls. “She would only say: ‘Why do you need to know this?’ This was connected to the repressions of the 1930s — many relatives were executed or exiled under Article 58 as ‘enemies of the people.’ Three years ago I discovered an astonishing fact in the records of the International Memorial. Formally, Sofya Dauletovna had been sentenced to the highest measure of punishment, even though she was never actually arrested. After her husband’s arrest, she was not allowed to leave the railway station in Almaty and was forbidden to travel out of Chimkent (now Shymkent). The chief physician of the hospital where she worked warned her that wives were often taken after their husbands. He helped her leave to become the head of a small hospital in the village of Shaulder.

While a case was being filed against her and a death sentence issued by the NKVD, she calmly worked as a rural doctor, not even knowing that she was officially registered as condemned to execution. Such were the paradoxes of the punitive system of that era — cases were processed formally, without interrogations or arrests, simply to fulfill the repression quotas.”

Original photograph by Shangeray Bokey.

“I keep the photographs in envelopes; I am afraid to take out the originals too often — the traces of time are already visible: the paper is crumbling, the emulsion is peeling,” she admits. “I have given copies to the museums of Uralsk and the regional archive, but the originals remain with me. Over the years of research, I have established contact with dozens of descendants of the dynasty scattered around the world. Some live in Russia — in Samara, Orenburg, Saratov and other regions. There are descendants in Germany and the United States. Many do not even suspect their lineage or cannot prove it, as archives were lost and documents burned during the years of repression.”

“Recently I found a photograph among relatives showing a young, handsome man whose features clearly reflect the characteristics of the dynasty. In the village of Zelyony Dol in the Samara region, I also located Madina Akyshyevna Bokey, the great-great-granddaughter of Khan Zhangir. When I visited her, she was nearly ninety, yet her mind was sharp, and she shared many family stories. Sadly, she is no longer alive.

People often come to me wanting to establish their descent from the dynasty. I always approach such requests with caution: I require documentary evidence, I study family archives, compare photographs. The more descendants we identify, the better — but I never make claims without proof.”

Sholpanai points to Dauletshakh Kusaypgaliyev.

“The Bokey dynasty gave Kazakhstan many outstanding figures,” she continues. “For example, Dauletshakh Zhusupovich Kusaypgaliyev, a descendant of Khan Abulkhair (line: Abulkhair → Nurali → Sultan Orman → Sultan Kusep → Zhusup → Dauletshakh), stood at the origins of the Alash party, participated in the Constituent Congress, and became part of the government of the Western branch of Alash Orda — the so-called Uil vilayat. He was a physician who dedicated 45 years to serving the people. He lived in the so-called Bukhar district (east of the Ural River), unlike the Bukey Horde, which was located between the Ural and Volga rivers. His wife, Aisha Mukhametgereyevna — a great-granddaughter of Khan Zhangir through the line of Sultan Seitgerey and Mukhametgeray — was also a doctor. Their daughter Gainnizhamal was repressed and survived the Abai Bazaar and Kerek camps in Southern Kazakhstan. Her husband, Yesengali Kasabulatov, became the first director of the Kazakh Medical Institute and one of the founders of the national healthcare system. Both were repressed under Article 58. Many descendants later became members of the State Duma of the Russian Empire. Alihan Bokeykhan, the leader of the Alash Orda movement, was among the most educated Kazakhs of his time.”

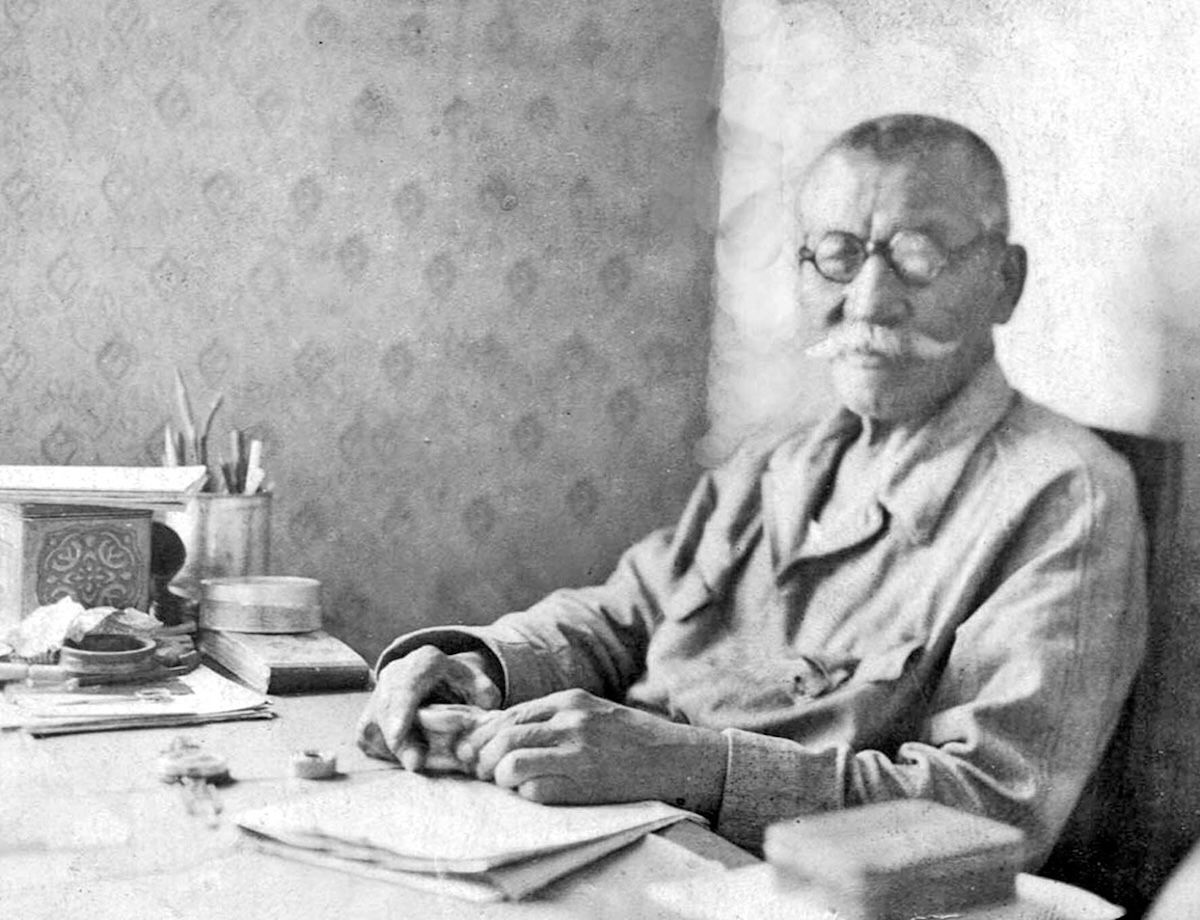

Alihan Nurmukhameduly Bokeykhan in his apartment one day before his arrest. Moscow, July 1937.

“It is important to note a historical confusion that many researchers still make,” Sholpanai explains. “At that time, two men named Bokeykhan, full namesakes and both descendants of Genghis Khan, were active in the political arena — but they came from two different dynasties. The first was Alihan Nurmukhameduly Bokeykhan, the leader of the Alash Orda movement, known as the ‘elder Bokeykhan.’ He descended from the line of Barak, the eldest son of Jadik (not to be confused with the dynasty of Khan Abulkhair).

“The second was Gabdulkhaqim Nurmukhameduly Bokeykhan, my grandmother Sofya Dauletovna’s husband, known as the ‘younger Bokeykhan.’ He was 26 years younger than Alihan.”

Gabdulkhaqim Bokeykhan, graduate of the Real Military School, Uralsk.

“Gabdulkhaqim was deputy chairman of the KirCIC (the Central Executive Committee of the Kirghiz ASSR), stood on the side of the Red Army, and supported Soviet power. He was a land-surveying engineer, the first plenipotentiary representative of Kazakhstan in Russia, and one of the founders of the Kazakh SSR, which declared the right of the nation to self-determination and the sovereignty of Kazakhstan. Even contemporaries often confused them, and today journalists and historians continue the confusion. The works of one are attributed to the other, although they stood on opposite sides of the political barricades. Both were repressed: Alihan was executed in 1937, and Gabdulkhaqim in 1938 according to the notorious Goryachev lists.”

Sofya and Gabdulkhaqim Bokeykhan, Uralsk, 1926.

“Sofya Dauletovna explained her husband’s surname this way: Gabdulkhaqim was born in a region that before the revolution was called the Bukey Horde — thus, the surname came from the geographic area, not from the name of Khan Bokey.”

“The representatives of the Bokey dynasty were distinguished by their tall stature, beauty, European manners, and deep education,” Amandzholova emphasizes.

Gabdulkhaqim Bokeykhan as a student at Zhangir Khan’s school (second row, second from left). Nurmukhamed Bokeykhan — father of Gabdulkhaqim, nephew of Zhangir Khan (second row, third from left). Imangali — secretary of Shangeray Bokey (second row, far right). First row, left to right: Bakash Bokey (Kassymov) — grandson of Sh. Bokey; Bakhytzhan Karataev — deputy of the 2nd State Duma; Jakhanşa Seidalin — member of the Alash party. In front of Shangeray Bokey’s house in Borsy, Ural region. 1905.

“In the group photographs, you can clearly see that the dynasty dressed in European fashion — men in suits with ties, women in lace dresses. They spoke several languages and received education in the best universities of the Russian Empire. At the same time, they remained Kazakh in spirit, preserving their connection to the people and their traditions. The dynasty gave the country not just wealthy individuals but true servants of society — doctors, teachers, public figures who sacrificed personal comfort for the common good.”

“Today, tremendous work is being done in Western Kazakhstan to preserve the historical memory of Khan Zhangir,” concludes Sholpanai Amandzholova. “Over the thirty years that I have been traveling there, an incredible amount has been accomplished. I am immensely grateful to the museum and the administration of the West Kazakhstan Region. The work of the ‘Khan Moldasy’ club is invaluable — they learned to read and decipher almost all inscriptions on the old gravestones. Now we know who is buried where. This is a huge layer of history studied through epitaphs. The mausoleum of the Khan has been fully restored, and during the restoration the years of his life were corrected: 1803–1845. One of the annexes of the mausoleum, several large rooms, has been dedicated to a museum exhibition of Shangeray Bukey’s estate. This is important because the estate itself was located in Kumys-Orda near the village of Savinka, on the border with Russia, where access is difficult. I have prepared family relics to donate to the museum — a pre-revolutionary cook book passed down through generations and antique household items.”

The representatives of the töre class truly played an important—yet still insufficiently researched—role in the history of our state.

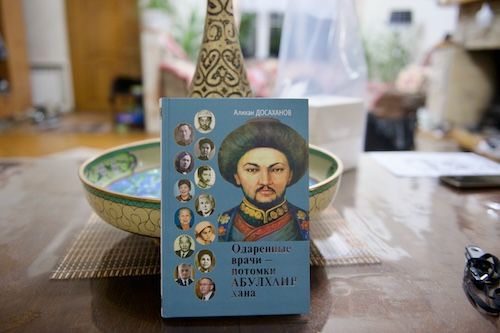

In his work, Alihan Khamzinovich Dosakhanov provides a detailed account of the contribution made by the Chinggisid descendants to the formation and development of healthcare in Kazakhstan. This is a serious academic study of the first Kazakh physicians, including members of the Asfendiyarov, Kusyapgaliyev, Shigayev, Bokeykhanov, and Seidaly families. The book contains a thorough reference section, extremely rare documents, and unique photographs. Published in a small print run, it will soon become a bibliographic rarity. Therefore, all history enthusiasts are encouraged to contact the author directly — Alihan Dosakhanov, +77015184199.

Shangerei Bokey shaped early Kazakh visual culture as the first photographer and educator. Story by Karlygash Nurzhan for Shanger.kz

Село Капал в Жетысу — место Шокана Уалиханова, Фатимы Габитовой и купца Атбасарова. Фоторепортаж о том, как жители возрождают архитектурное наследие.

Comments

Портреты загоаорили