From Horse to Kazy — The Kazakh Autumn Tradition of Sogym

VoxPopuli and Karla Nur

Since ancient times, the Kazakh people have slaughtered livestock before winter. The tradition of preparing sogym (winter meat reserves) has existed for centuries. Our wise ancestors realized that it was most profitable to slaughter livestock in late autumn. First, there would be enough food for the entire winter. Second, storing meat in winter is effortless — the cold preserves it. Third, animals gain their greatest weight in autumn. Kazakhs divide horses into three categories: riding horses (racehorses), working horses, and those intended for sogym. Racehorses are never slaughtered — they are respected. Working horses are slaughtered only in rare cases. Usually, horses specially raised for this purpose are used for sogym. They are grazed and fattened like other livestock, and unlike racehorses, they are not given names.

Farmer Zhūman looks toward the pasture where his livestock graze. He has tended them for 40 years. Now he has his own farm with several dozen horses, cows, and sheep. Every autumn Zhūman slaughters a horse for sogym. Today is exactly that day.

Zhūman’s son Yerlik goes to the corral with a lasso to catch a horse.

Only after several attempts does he manage to throw the lasso.

The main goal is to tie the rope to a tree. Yerlik’s younger brother Daniyar helps by driving the horse with rods.

Finally, with combined effort, Zhūman and his sons manage to wrap the rope around a tree. Then they tighten and pull the rope to bring the horse to the ground.

As soon as it falls, the slaughterer Beisenby tries to press the horse’s head to the ground. Once the horse is securely tied, the lasso is moved from the neck to the head, hooking it behind the teeth to stretch the animal’s neck properly.

Before starting the ritual, everyone silently says a short prayer. When the animal is completely still, Yerlik removes the lasso and prepares the area for butchering. The horse is carried to a specially prepared place.

Before beginning the work, the slaughterers wash their hands and start.

After butchering, the meat is taken home immediately to avoid attracting flies and dogs. The brisket and internal organs are suitable for kuyrdak and kazy.

While the men are butchering the meat, kuyrdak is already being prepared in the kitchen. In the photo, Zhūman's relative Rezhan cuts meat for the dish. Kuyrdak uses lungs, heart, and a bit of brisket. The meat is cut into medium-sized cubes.

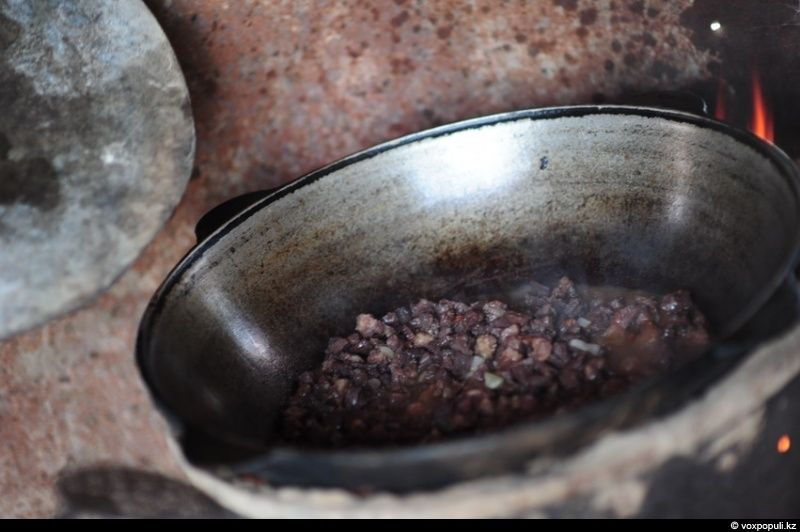

A cauldron is placed outside under a canopy.

First the meat is added, followed by onions and garlic; sometimes tomatoes are added for flavor. The cauldron is tightly covered and simmered over medium heat.

While Rezhan works in the kitchen, other women in the yard clean intestines and stomach. Apisan cuts the intestine with a knife, and Kuleymash holds the other end. Both are neighbors of the farm owner.

All internal organs are thoroughly washed in salty water. Salt helps remove dirt and mucus from the intestines.

The stomach (karyn) is cut open and cleaned.

The meat on the ribs will become future kazy. The ribs are removed whole, without splitting.

The most valued cuts of horse meat are zhaya (pictured), kazy, and karta. Zhaya is cut from the back thigh of the horse. Since ancient times Kazakhs have never eaten fresh meat immediately — it is first salted and air-dried, and only then boiled and eaten.

At the end, the men clean the slaughter area.

The women continue cleaning the intestines. “My father was a herdsman for about 50 years. You could say we are a dynasty of herdsmen, and our traditions are passed from generation to generation,” says Apisan.

Evening falls on the farm, and the chickens that hid from the harsh sun now come out into the yard.

One of the farm dogs — Kutbol.

Kuyrdak is almost ready.

And the samovar begins to boil for tea.

Zhūman hugs his relative Rezhan.

In the farmhouse, the table is already set. Real kuyrdak is cooked without potatoes.

After dinner Apisan and Kuleymash put aside the cleaning and begin preparing kazy.

First, the filling for kazy is cut into strips from the horse’s ribs.

The meat is seasoned with a special mixture of salt, garlic, and black pepper. Some women use their own secret blend.

The seasoned meat is pushed into the cleaned intestine by hand. For kazy, a special twelve-finger intestine about 10–12 meters long is used. The meat is packed tightly into the intestine, taking care not to tear it.

Kazy is made 60–70 cm long, and the remaining intestine is cut off. The end is “stitched” with a toothpick. In ancient times, when toothpicks didn’t exist, our ancestors used reed sticks.

Umit watches the young women work with interest. “I am 75, and in my family all the men were herdsmen too. Helping my mother, I learned to make kazy in childhood,” she says. After a few minutes, unable to sit still, she begins helping herself.

At the end of the work, the kazy is placed in a dry area to absorb the seasoning. One of the most beloved Kazakh delicacies can then be considered ready.

The original version of this material was published on the Voxpopuli.kz portal (before its closure in 2023). Author Karlygash Nurzhan restored the text and photos from her personal archive to preserve documentary and historical materials.

A documentary story of Koldy’s fishermen, their lives and traditions…Photo report by Karlygash Nurzhan for Shanger.kz

Верблюжье ферма в Казахстане: труд, забота, традиции и редкие кадры рождения верблюжонка. Фоторепортаж для Shanger.kz

The Kazakh diaspora in Turkey: migration history, daily life, traditions and human stories… Фоторепортаж Карлыгаш Нуржан для Shanger.kz

Село Капал в Жетысу — место Шокана Уалиханова, Фатимы Габитовой и купца Атбасарова. Фоторепортаж о том, как жители возрождают архитектурное наследие.

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!